‘Women Prisoners’ Defence League’

August 2022 marks the centenary of formation of The Women Prisoners’ Defence League according to a document found in 47 Parnell Square sometime in the 1970s, now in a private collection:

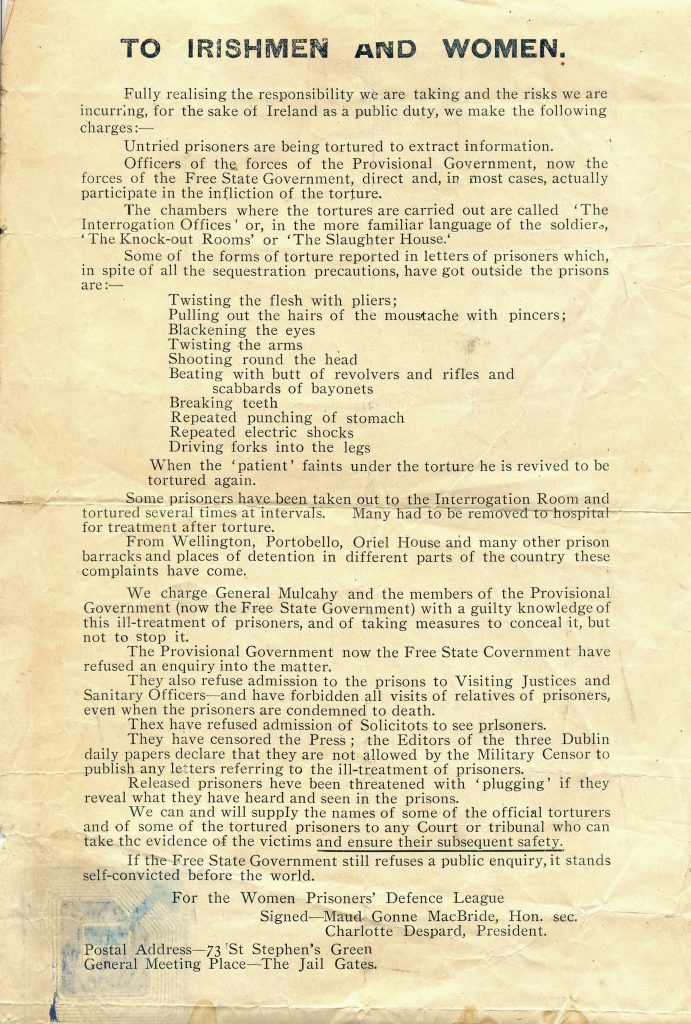

The Women’s Prisoners’ Defence League was started in August 1922, informally outside the gates of Mountjoy Jail, Dublin, by the mothers, wives and sisters of Republican Prisoners. Outside the gaol gates then, were crowds of women endeavouring to obtain news of their missing sons, husbands and daughters, or to bring food and clothing to those whose location they had discovered. No visits were allowed, no information supplied. One woman was shot through the leg while trying to get news of her husband outside Wellington Barracks (later Griffith Barracks now Griffith College). One young lad was killed outside Mountjoy Jail, while accompanying a woman who was seeking news of her son. Terrifying stories, but too tragically confirmed later, of the beating and torture of prisoners for information, circulated. The constant sound of firing in the jails and wounding of prisoners made the need of a Prisoners’ Defence League obvious and urgent. The League was formally confirmed and a committee appointed of which Mrs Despard was President and Maud Gonne MacBride Sec. at a mass meeting of women in the Round Room of the Mansion House.

Its objects – to obtain the release of Republican Prisoners and pending release, prisoner of war treatment, and help to families to get news of their relatives in jails. In furtherance of these objects the League held weekly meetings in the war ruins of O’Connell Street, where all prison news was pooled and given out. It organised meeting in other places and poster parades, street painting etc. It sent deputations to the Dublin Corporation and to the Red Cross. It obtained the setting up of a sworn inquiry by the Lord Mayor, into the treatment of Republican Prisoners, which enquiry was banned by the Irish Free State Government on the third day of its sittings … the League worked indefatigably, taking up the meetings of trains, visiting hospitals and billeting …

Then the League organised a service for watching the courts and provision of food to Political Prisoners in the Bridewell. No proper provision is made for feeding prisoners in the Bridewell and those sent from the country who have no relatives to look after them in Dublin, and no money to buy food, single great hardships … All the work of the League is voluntary.

A full transcription of this document can be found: here.

Dr Cormac Moore, Historian-in-Residence, Dublin City Council focusing on the area of Dublin North Central writes on The Women Prisoners’ Defence League which was formed in August 1922:

During the Civil War, approximately 13,000 republicans were imprisoned or interned, with over 500 of them being women. With such numbers, the prison services were unable to cope. Prisons became full and cramped, with up to six people confined to one cell in some cases. There were constant complaints about diet, disease and overcrowding in the prisons. Although visits were not allowed, news filtered through of prisoners being tortured. There was also great hardship for the families of those imprisoned, the incarcerated being the main breadwinners in most cases.

The Women Prisoners’ Defence League was founded, seeking prisoner-of-war status and better conditions for the prisoners and internees. Charlotte Despard, the long-time suffragette and advanced nationalist (sister of the former Viceroy of Ireland John French), became president and Maud Gonne MacBride, political activist, became secretary. Both Despard and Gonne MacBride had been friends for many years, Despard moved permanently to Ireland and they bought a house together, Roebuck House in Clonskeagh, Dublin in 1922.

The Women Prisoners’ Defence League held protest meetings in places such as the Mansion House and processions on O’Connell Street, highlighting the plight of prisoners and Members of the League interrupted Dáil Éireann proceedings and pressurised Dublin City Council to commission a report on the conditions of republicans incarcerated. Vigils were also held outside the prisons where republicans were imprisoned.

Cormac Moore, has a PhD from De Montfort University in Leicester and is the author of Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland (2019), The Irish Soccer Split (2015) and The GAA V Douglas Hyde: The Removal of Ireland’s First President as GAA Patron (2012). He is currently writing a book on Laois and the Irish Revolution due to be published in 2023, and is an editor of the Atlas of Irish Sport, also due to be published in 2023. He is a regular media contributor and currently writes a monthly column for the Irish News on 100 years of partition.

Dr Mary Muldowney

Historian-in-Residence Dublin City Council (focusing on the area of Dublin Central). For Mná100 she looks at the work of the Women Prisoners’ Defence League with a special focus on women arrested during the Civil War.

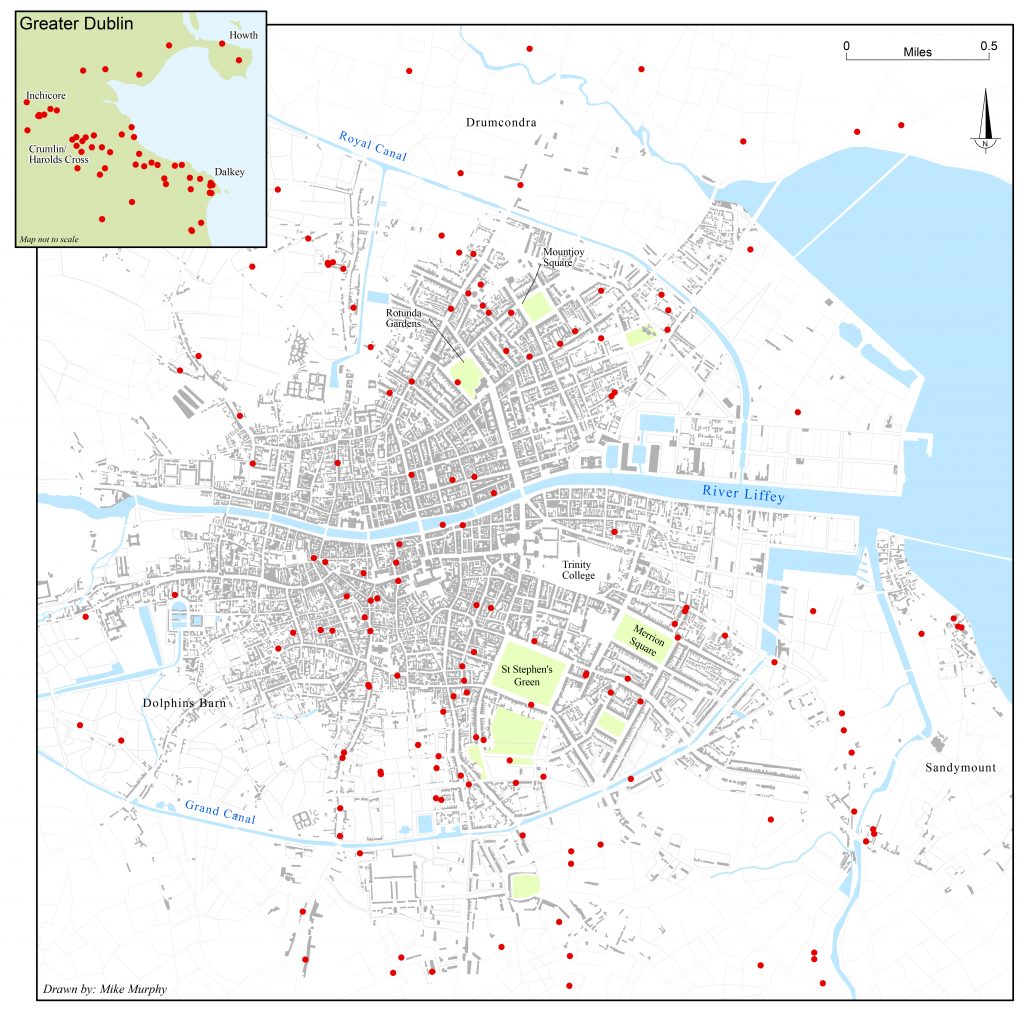

The map in the Atlas of the Irish Revolution showing the residences of the women interned between 1922 and 1923, indicates that the prisoners lived predominantly in more affluent areas. There were a small number of working class women who claimed pensions and the map highlights how few residents from the slum areas of Dublin City had were imprisoned.

Dr Mary Muldowney focuses on two women Kathleen Barrett (nee Connolly) and Molly (Mary) O’Reilly.

There were women from such areas in other parts of the country who claimed pensions but mainly from the 1916 Easter Rising and less frequently from activity during the War of Independence. It was certainly the case that the Irish Free State imprisoned many more women than the British had, in a shorter time frame.

Anti-Treaty Cumann na mBan and the IRA worked together preparing ambushes on the Free State army. While there is no evidence that any women took part in these ambushes, they did play a significant role in supplying, storing, cleaning and priming the guns. They also acted as couriers and many were arrested while carrying IRA intelligence documents or hiding them in their homes.

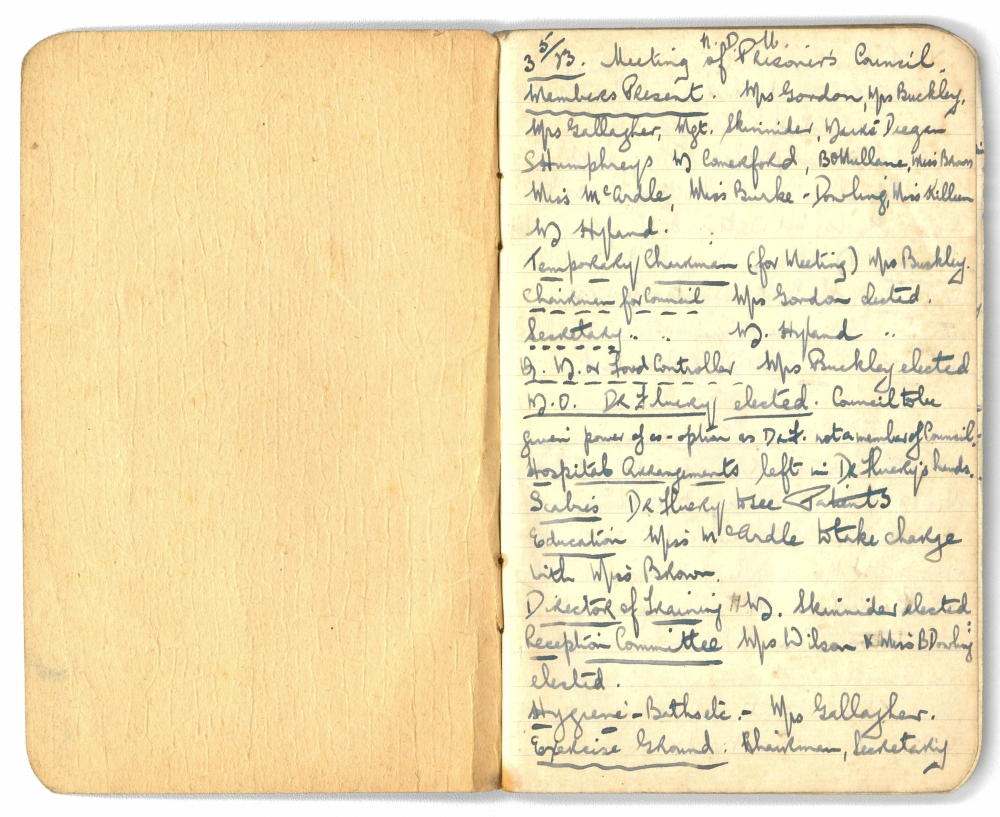

During the period of the war and for several months following the arms dump that ended it, female political prisoners were held at Kilmainham Jail, Mountjoy Jail and the North Dublin Union, which had been used as a British Army barracks in the War of Independence. In each of the three prisons, the women elected a prisoner’s council whose role was to deal with the authorities but also to exert discipline, even though not all of the prisoners were members of Cumann na mBan.

Museum/OPW. KMGLM.20MS-1B43-28

In the course of the War of Independence, the activities of the members of Cumann na mBan in working with the IRA gave them a sense of confidence in their abilities, particularly among the Dublin based republican women who dominated the anti-Treaty Cumann na mBan.

Kathleen Barrett (nee Connolly) was one such young woman, from a family of eight sons and eight daughters, all of them dedicated Republicans. Kathleen was a member of the Irish Citizen’s Army (ICA) during the 1916 Easter Rising and a trusted messenger for the City Hall Garrison, where her brother Sean was shot and killed. She was imprisoned in Ship Street, then transferred to Richmond Barracks and subsequently to Kilmainham Gaol, from where she was released on 09 May 1916.

Courtesy of Kilmainham Gaol Museum KMGLM.18PC-1B53-02

She joined the Central Branch of Cumann na mBan and was active in collecting for the National Aid and Volunteer Dependents’ Fund. She campaigned for Sinn Fein in the 1918 General Election and was also active in the anti-conscription campaign earlier that year. During the War of Independence she visited wounded volunteers in hospital and took part in vigils outside Mountjoy during hunger strikes and executions.

In 1922 she was on the anti-Treaty side and served in various anti-Treaty outposts during the Battle for Dublin. She was a courier for the Republican Envoy in London, Art O’Brien. In March 1923, she was arrested in London and sent back to Dublin to be interned in Mountjoy and the North Dublin Union. See Kathleen Barrett’s Bureau of Military History Pension Record here.

Molly (Mary) O’Reilly had taken part in the soup kitchen in the basement of Liberty Hall to feed the starving families of the locked-out workers during the Dublin Lockout of 1913. She was asked by James Connolly to raise the flag of the Republic over Liberty Hall before the 1916 Easter Rising, when she was only fourteen years of age. She was a local girl from Gardiner Street who had been a member of Clann na nGaedheal, the Republican girl scouts, since she was eleven. She was a member of the Irish Citizen Army in 1916 and she acted as a courier during Easter Week.

Molly went on to spy for Michael Collins in the course of the War of Independence where she was able to use her job in the United Services Club for British soldiers as a cover for her intelligence gathering activities.

In 1922 Molly was arrested and imprisoned for her opposition to the Treaty. She went on hunger strike during her time in Mountjoy Jail. She was released in November 1923.

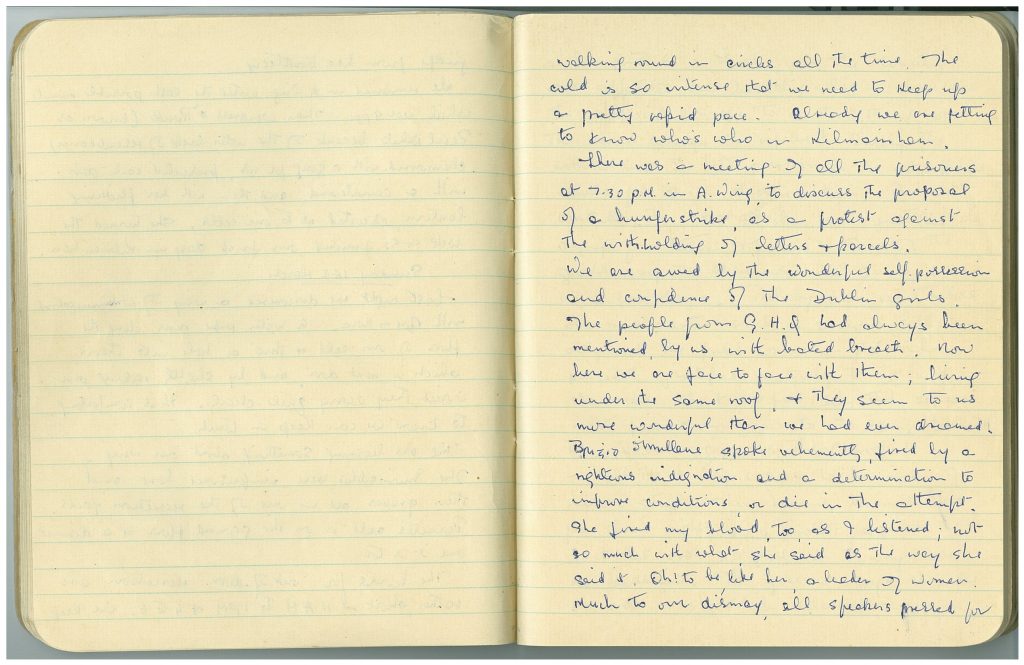

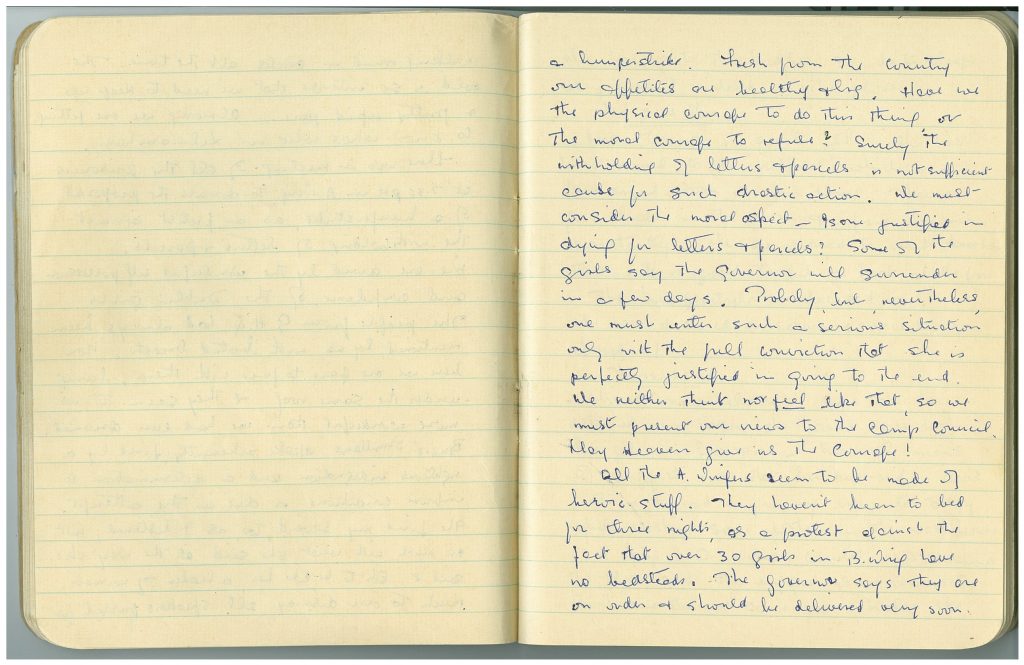

Hannah Moynihan, a young woman from Kerry wrote in her diary about how she and others from a rural background felt about the leaders. The leaders were based in Dublin, General Headquarters (known as GHQ), as was the case with the IRA Hannah Moynihan and her comrades were not alone in feeling intimated by the more zealous prisoners. There was tension between the anti-Treaty IRA and the Dublin-based army GHQ because of a lack of consultation, particularly after the Treaty was signed.

We are awed by the wonderful self-possession and confidence of the Dublin girls. The people from GHQ had always been mentioned by us with bated breath. How here we are face to face with them; living under the same roof and they seem to us more wonderful than we had ever dreamed.

Hannah Moynihan from above diary entry.

Much to our dismay all speakers pressed for a hunger strike. Fresh from the country our appetites are healthy and big. Have we the physical courage to refuse? … We must consider the moral aspect – is one justified in dying for letters and parcels?

Hannah Moynihan from above diary entry.

Political prisoners were obliged to keep their accommodation clean but the Cumann na mBan prisoners’ councils refused to this, although the male prisoners obeyed the rules. The International Committee of the Red Cross sent a delegation to review the conditions in which anti-Treaty prisoners were kept. In the report issued after the inspection, the author considered that the women prisoners’ focus was on their demands for release rather than their conditions and as this was outside the terms of reference for the inspection, it did not merit a visit to the three jails in which women prisoners were held.

Mary Muldowney received her Ph.D from Trinity College Dublin. Her book based on her thesis, The Second World War and Irish Women was published Irish Academic Press (2007). Her publications during the Decade of Centenaries include chapters for each of the History on your Doorstep books published by Dublin City Council and she co-edited the most recent volume. She edited and contributed chapters to 100 Years Later: the Legacy of the 1913 Lockout in 2013.

Mary has written and presented online lectures and talks on a broad range of aspects of Dublin’s history, particularly in relation to the revolutionary decade. They are accessible through the Dublin Central Historian-in-Residence Facebook page and have been widely shared. (@dublincentralHIR) As a member of the Expert Working Group for Grangegorman Histories, she is directing a pilot oral history project. (Grangegorman Histories @ ria.ie)

Mary’s interviews with activists in the pro-choice movement in Ireland 1983-2010 are publicly accessible through the Digital Repository of Ireland. (The pro-choice movement in Ireland from 1983-2010.)

She is currently working on an oral history of the Dublin Cattle Market and an oral history of the National Union of Vehicle Builders’ branch of the Amalgamated Transport and General Workers Union. She is a member of the organising committee of the Irish Labour History Society and was recently appointed as a co-editor of Saothar, the internationally recognised journal of the ILHS. (www.irishlabourhistorysociety.com)

Dr Lia Brazil, Research Fellow, Nuffield College, University of Oxford.

Lia Brazil is a postdoctoral research fellow at Nuffield College, she is working on the AHRC-funded project, ‘International NGOs and the Long Humanitarian Century: Legacy, Legitimacy and Leading into the Future‘ alongside Professor Andrew Thompson and Professor Mike Aaronson. This project was commenced in 2021 and is due for completion in 2024.

Here Lia Brazil contributes the following on Women’s Prisoners Defence League and the humanitarian zeitgeist: Their International Activities in 1922 and 1923.

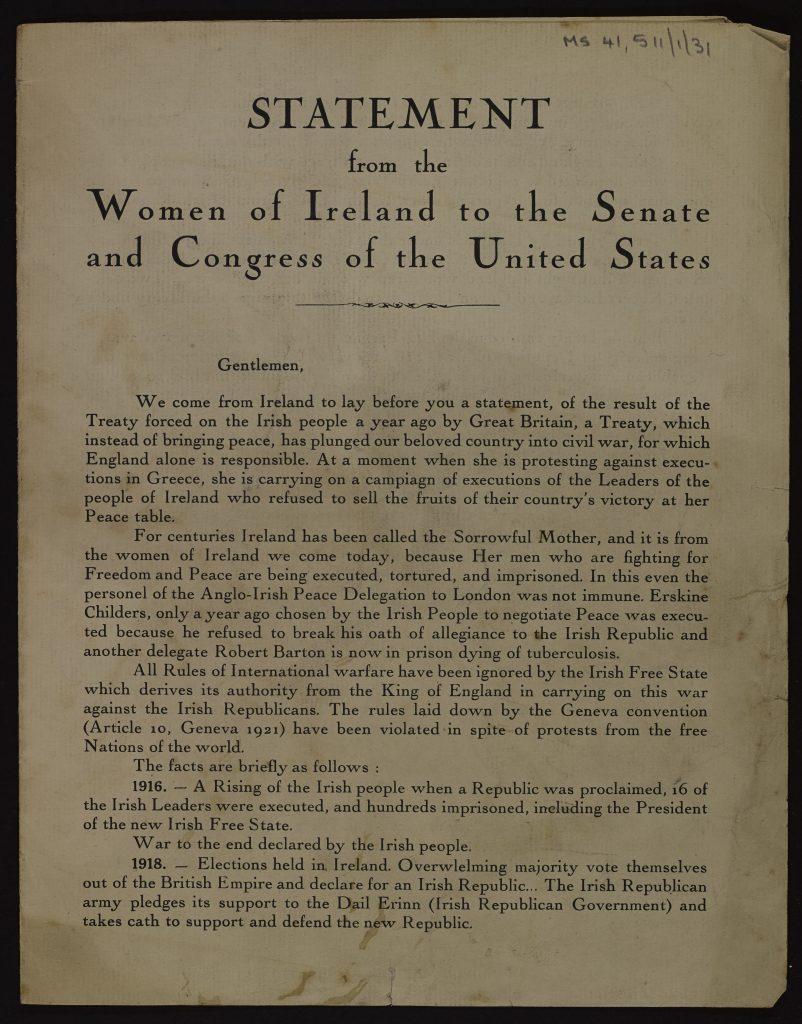

Statement from the Women of Ireland to the Senate and Congress of the United States. Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland. MS 41,511/1/31

The Women’s Prisoners’ Defence League were not content confining their appeals to Ireland alone. Its founders Charlotte Despard and Maud Gonne MacBride were both fluent in French and connected to international organisations throughout Europe, they simultaneously launched their protests on an international stage. Leveraging their connections through women’s organisations like the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), they sought intervention on behalf of Irish republican prisoners from the International Committee of the Red Cross and the League of Nations.

The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom evolved out of an International Peace Congress held in 1915 by women opposed to the ongoing First World War. Charlotte Despard soon became one of its most active members. She was one of a five-woman delegation sent by the WILPF to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 to protest the terms of the post-war treaty. A former Labour party candidate, she was a well-known activist in British leftist circles, particularly as a founder of the non-violent women’s suffrage organisation, the Women’s Freedom League.

By the outbreak of the civil war, Despard was living with Maud Gonne MacBride, the other founder of the WPDL. As early as 1914, Gonne MacBride had contacted the International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva in the hope of establishing an independent Irish Red Cross Society, affiliated with her own nationalist women’s organisation, Inghinidhe na hÉireann.[1] Since 1864 the International Committee of the Red Cross had held a mandate under international law to uphold the Geneva Conventions, while during the First World War it was recognized by all belligerents as a neutral intermediary and advocate for the rights and protections of prisoners of war. During the conflict Red Cross delegates inspected prison camps and campaigned for better conditions for prisoners.

Despard and Gonne MacBride were aware of the ability of international organisations like the Red Cross to lobby governments for the humane treatment of prisoners. In the aftermath of the war, humanitarian organisations proliferated throughout Europe, aiming to rebuild the continent, improve conditions for veterans and secure the release of thousands of prisoners of war detained worldwide. Irish activists had already tapped into this humanitarian zeitgeist during the War of Independence (1919 – 1921).

In the United States, women marched in Washington demanding American Red Cross intervention in Ireland. For more context see (https://www.mna100.ie/centenary-moments/toward-america/).

Membership of the Irish White Cross overlapped with that of the Women’s Prisoners’ Defence League. The women involved had learnt how to attract media attention through carefully planned public events and their actions had resulted in thousands donated for humanitarian relief in Ireland. After the outbreak of Civil War in June 1922, they sought humanitarian intervention, rather than relief for republican prisoners.

After the commencement of the Provisional Government’s execution policy in November 1922, petitions were presented before the United States Congress, the Peace Conference at Lausanne, and the International Committee of the Red Cross, in Geneva. In these petitions and protests, members of the Women’s Prisoners’ Defence League invoked the rhetoric of humanitarianism and suffering to draw the eyes of the world to Irish Free State prisons and internment camps.

Petitions like this one claimed to be made on behalf of the women of ‘Sorrowful Mother’ Ireland, to represent the mothers and wives separated from their sons and husbands. Prisons conditions were intolerable, the WPDL alleged in the petitions, and “beyond belief in a civilised age”. They claimed that the Free State was violating the rules of international warfare, referring specifically to the 10th International Conference of the Red Cross, 1921, where the organisation expanded its remit to encompass protection for prisoners during civil wars and internal conflicts. Though the WPDL seemed uncertain of the legality of this decision – referring to it as part of the Geneva Conventions, rather than a binding conference resolution – they insisted its spirit had been violated by the Irish Free State. They demanded prisoner of war treatment be internationally guaranteed for republican prisoners, hoping to halt the Free State’s execution policy. Their documents insisted that Britain was responsible for continuing the war and demanded intervention ‘in the name of humanity’. As a result of their efforts, in April 1923, the Red Cross travelled to Ireland to investigate prison conditions, though its final report ultimately exonerated the Irish Free State.

The members of the Women’s Prisoners’ Defence League are striking for their use of the emerging rhetoric of international law and prisoner rights. Aware of previous Red Cross missions in Budapest, Poland, and Ukraine, they saw the potential for intervention on humanitarian grounds to improve conditions for republican prisoners. Similarly, their emphasis on their maternalism as justification for their humanitarianism mirrored the efforts of women humanitarians throughout post-war Europe, particularly Eglantyne Jebb and the Save the Children Fund.

Despite being under constant threat of imprisonment themselves, members of the WPDL remained internationally mobile throughout the civil war, with women like Albinia Brodrick, Kathleen O’Brennan and Kathleen Lynn travelling to Geneva during the conflict. Here, they were received by official dignitaries, while their efforts were reported on in international media. Initial petitions highlighted their role as mothers and wives, yet as the war progressed, they often drew from their own prison experience to highlight the Free State’s mistreatment of both men and women prisoners. During the Irish civil war, when many in Europe remained uncertain of conditions and affairs in Ireland, the WPDL provided an invaluable link between Ireland and the wider world.

[1] Meaning ‘Daughters of Ireland’, Inghinidhe na hÉireann, (1900 – 1914) was later amalgamated with Cumann na mBan.

Lia Brazil completed her PhD entitled, “International Law and the Rule of Law in the British Empire, 1899 – 1921“ at the European University Institute, Florence in 2021. This project focused on the use of international legal arguments on the ground during the Second South African War (1899 – 1902) and the Irish struggle for independence (1916 – 1923). She studied for her BA at Trinity College Dublin, and her MA in European History at University College Dublin. Her current research looks at how INGOs were harnessed by actors during conflicts, with particular focus on the Red Cross movement. Her ongoing research on the International Committee of the Red Cross and women’s internationalism during the Irish civil war has been funded by the Irish Legal History Society.

Marie Coleman, ‘Cumann na mBan Opposes the Anglo-Irish Treaty: Women Activists During the Civil War’, in Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry (eds) Ireland 1922: Independence, Partition, Civil War (Dublin, Royal Irish Academy, 2021)

John Dorney, The Civil War in Dublin: The Fight for the Irish Capital, 1922-1924 (Kildare: Merrion Press, 2017)

Diarmaid Ferriter, Between Two Hells: The Irish Civil War (London: Profile Books, 2021)

Irish Times

Irish Independent

Belfast News Letter

Cork Examiner

Evening Echo

Strabane Chronicle

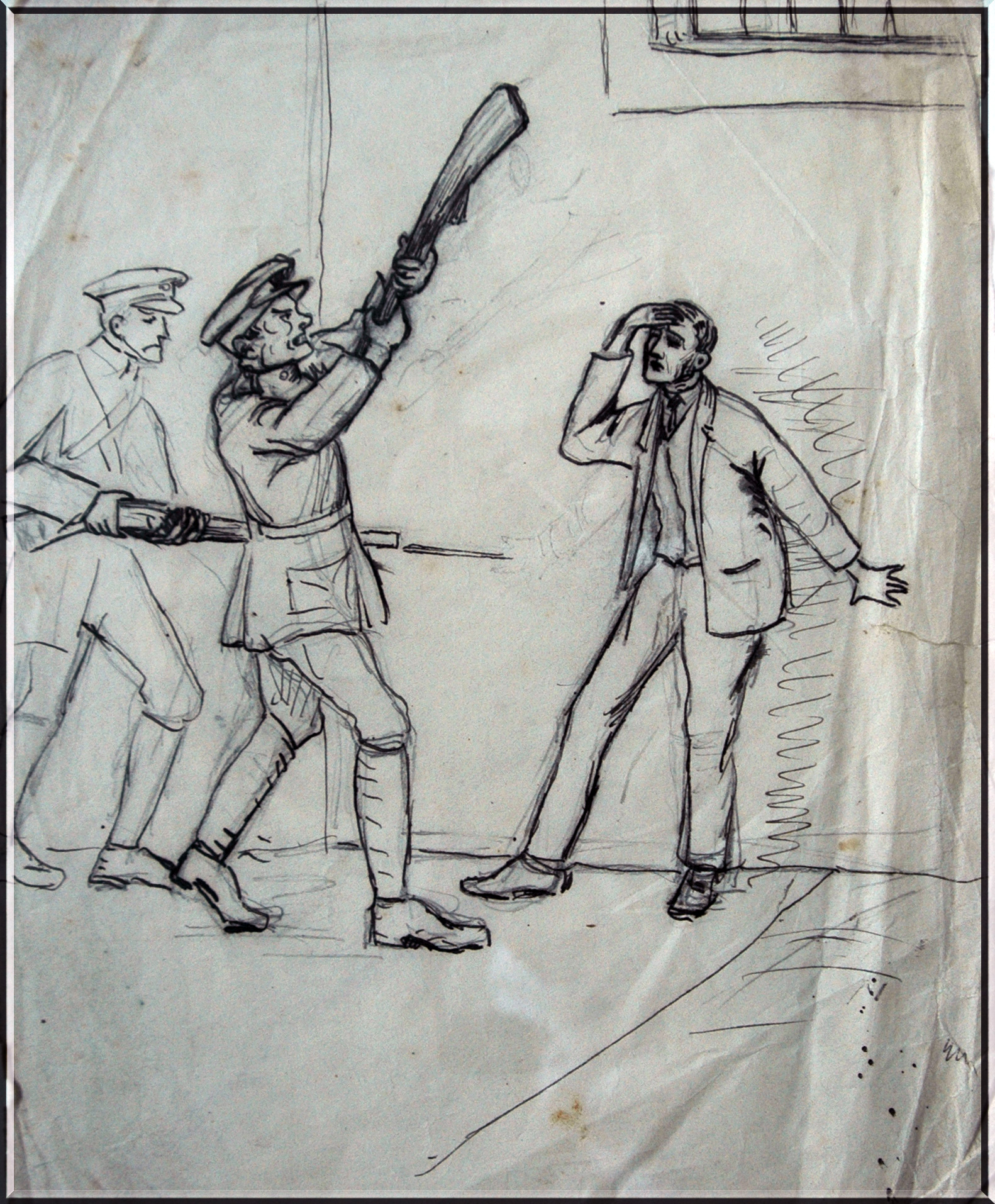

Feature image: Sketch by Countess Markievicz. Courtesy of Lissadell House.