The Handover of Dublin Castle

Mná100, in association with The Royal Irish Academy, marks the centenary of the Handover of Dublin Castle, one of the key events to be remembered as part of the Decade of Centenaries programme for 2022.

Dr Kate O’Malley is co-author with Dr John Gibney of the Royal Irish Academy’s latest publication The Handover: Dublin Castle and the British Withdrawal from Ireland, 1922. In this piece, we share excerpts from this book, and focus on some of the women who were in Dublin Castle on the 16 January and those women who paved the way for ‘the Handover’.

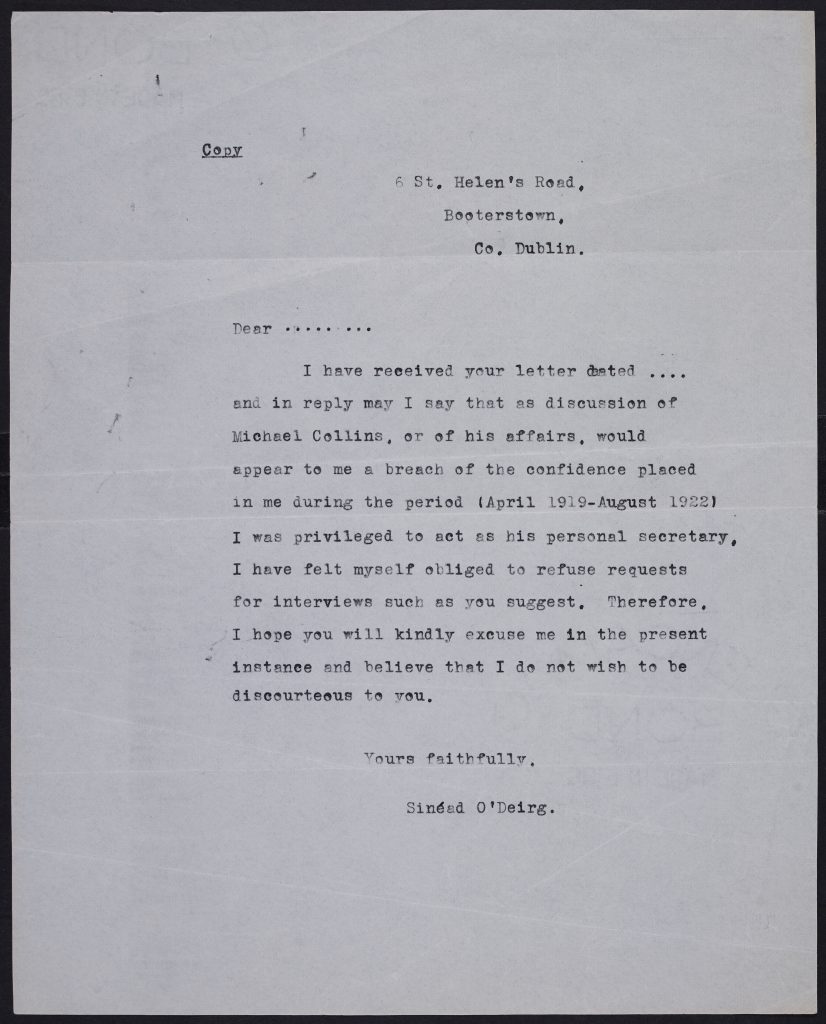

We hone in on the women who were in Dublin Castle on 16 January 1922. Many women were employed as secretaries, both as part of the British Administration in Dublin Castle and attached to the new Irish Provisional Government. This includes Sinéad Mason, Michael Collins’s Personal Secretary, who was likely to have been in attendance on the day of the Handover.

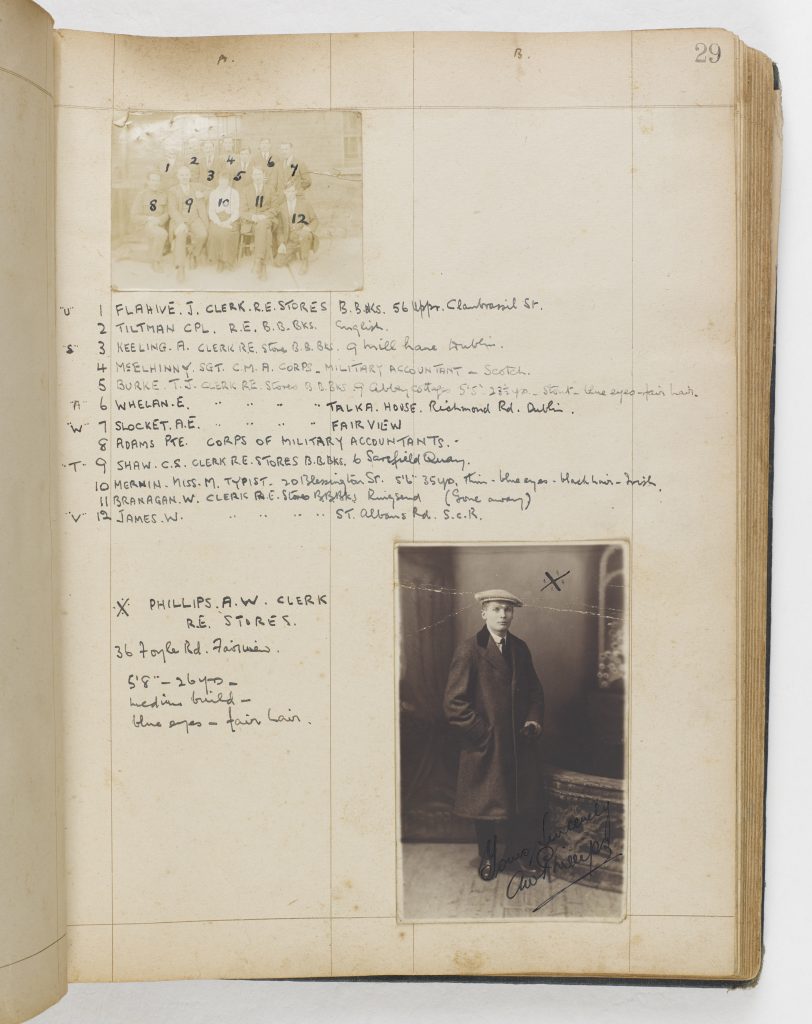

We profile some of the women who were part of the British Civil Service including, Lily Mernin, nicknamed the ‘Little Gentleman,’ by Michael Collins, as a shorthand typist in the intelligence section in Dublin Castle during the campaign of independence, Lily Mernin put her life at risk on many occasions as she smuggled out documents and shared information. Her role remained secret during her lifetime, but the fullness of her story has come to light through the work of historians such as Professor Marie Coleman, Queen’s University Belfast, who has written her biography for the Dictionary of Irish Biography (DIB), a project of The Royal Irish Academy.

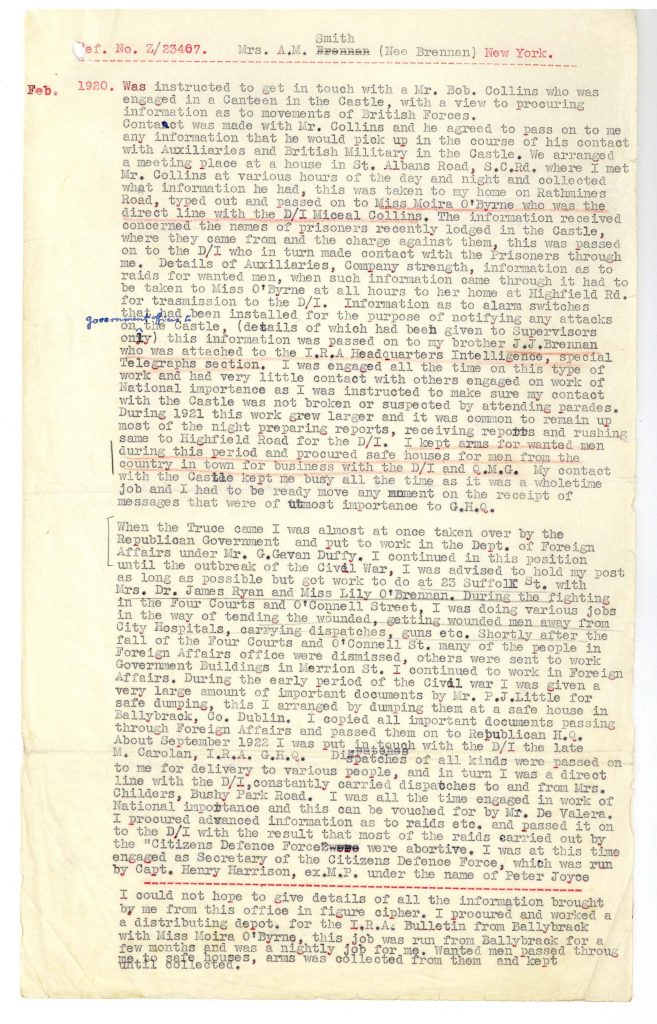

We document the role of the rank and file, whose military service pension files reveal their participation in the events that led to the Handover such as Annie Mary Smith (née Brennan). Annie Mary Smith was an informant within Dublin Castle staff and she supplied the information she received to Michael Collins in his capacity as IRA Director of Intelligence.

We look at the women who worked in the Dáil Éireann structures (often without pay) when it was a proscribed organisation. Some women who worked in the shadow government, were given employment once the Truce was called, a small number worked with the Provisional Government, and later in the Irish Free State. Many worked in a temporary capacity and were only made permanent in 1932.

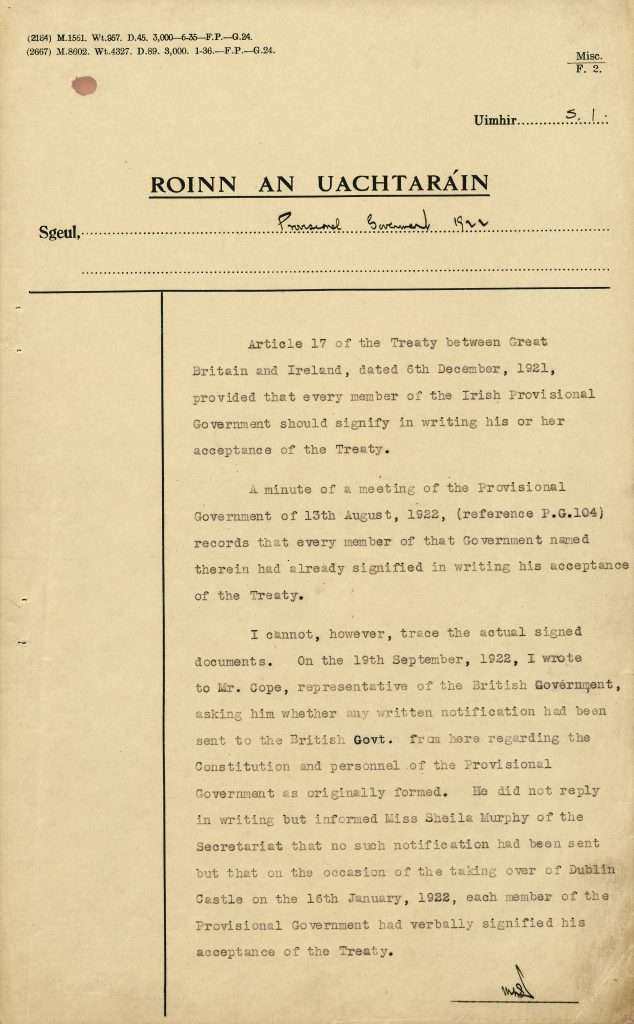

We encounter the twenty four year old civil servant Shiela Murphy, who was part of the Dáil Éireann staff who worked in Roinn an Uachtaráin, office of the President of the Provisional Government and later in the Department of External Affairs. She was the highest-ranking female diplomat by the end of her career in 1964 as written by Dr Michael Kennedy, Executive Editor and head of the RIA’s Documents on Irish Foreign Policy series.

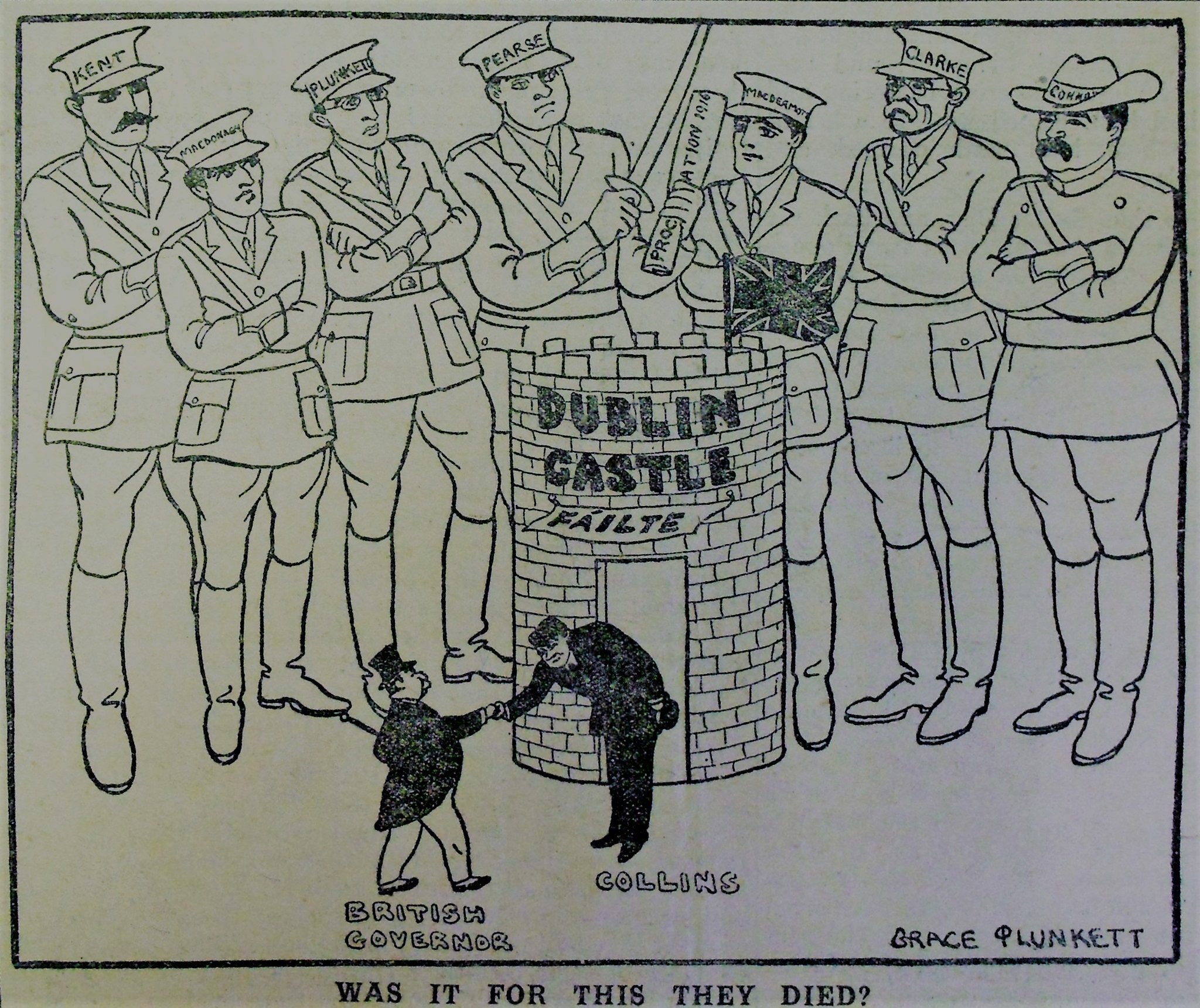

We also consider the reaction of two women who opposed acceptance of the Articles of Agreement between Great Britain and Ireland. Kathleen Clarke TD who tabled her thoughts on the Handover of Dublin Castle as a motion in City Hall in her capacity as a Sinn Féin Councillor on Dublin Corporation, and Grace Plunkett whose cartoon is printed above. Frances Clarke details their lives in her RIA Dictionary of Biography entries.

Finally, we include a discussion of the place of women in the British press coverage of the Handover by Dr Elspeth Payne.

First, for some context, we are sharing extracts from The Handover: Dublin Castle and the British withdrawal from Ireland, 1922 by Dr John Gibney and Dr Kate O’Malley, which provides us with a comprehensive overview of this period in our history:

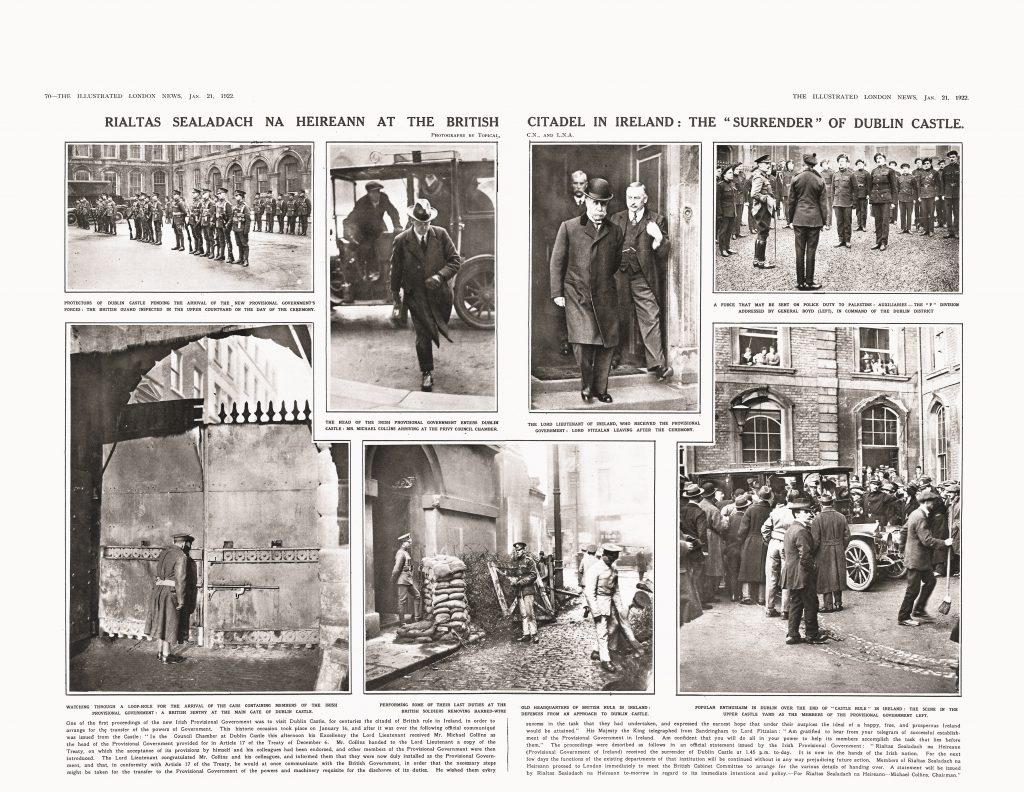

On the 16 January 1922 the Freeman’s Journal masthead that stretched across an entire page read: ‘Dublin Castle falls after seven centuries’ siege.’ Dublin Castle was where the British Government in Ireland was based, and so the significance of what was reportedly due to take place there on 16 January 1922 would not have been lost on the readers of the morning papers that day or on those who may have heard the news called out by news vendors on the streets.

The members of the new Provisional Government are ‘representatives of the Irish nation’ who will ‘deal with that hotbed of bureaucracy … and misrule’ ‘in accordance with the wishes of the Irish people’ and will ‘end forever the iniquities of ‘Castle’ so called government.’ Following the Treaty, power had to be handed over by the British, who were leaving, to the Irish.

Ireland in 1921-22 was formally a part of the United Kingdom rather than the British empire, but aspects of the way in which it was governed, and of the institutions by which the British governed it, as well as how the British themselves viewed it, were more akin to those found elsewhere in the empire; moreover, the ways in which the British responded to the Irish revolution were shaped by the commitments to the empire, and in the post-war world more generally. Ireland was not the only imperial problem faced by the British in the aftermath of the First World War. Another was Egypt, where the outbreak of a revolution in 1919 had coincided with the war of independence in Ireland and, unsurprisingly, it attracted a lot of coverage in Irish newspapers as a result, Irish nationalists saw parallels with the revolutionary activity and its repression there.

The world’s attention was directed at India too in 1919, when the Amritsar Massacre occurred in the Punjab. British repression in colonial India had a similar impact on the Indian nationalist moment as the aftermath of the Easter Rising had in Ireland. The independence struggle in India was the one most commonly linked with that of Ireland and throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries many links between the two movements were established, especially by women activists. For further reading see this History Ireland article.

Back in Dublin in January 1922, the new Irish Government-in-waiting, the Provisional Government established by the Treaty, had a pressing task to travel to Dublin Castle – the complex of buildings that embodied British rule in Ireland – and take control of the administration based there. The details of how this would happen were unclear: ‘It is not known whether a formal transfer of authority will be open to the press or will be mainly a private function. In any case, it will be at most a formality.’ The Irish Times, 16 January 1922.

The Castle lay behind the intersection of Dame Street and George’s Street, adjacent to the commercial district around Dame Street (in which insurance and banking quite literally loomed large) and the western fringe of the retail district centred around the more high- end shops of Grafton Street. Dawson Street was the eastern edge, and so the Provisional Government would have traversed both districts going to and from the Castle. Crowds had assembled near the Castle from early that morning, though they were unsure of what time the event was to take place. The Dublin Metropolitan Police regulated the traffic in the vicinity. Barbed wire had been removed from the approaches to the Castle and inside the complex some of the canvas screens erected for protecting the Castle buildings from view were being taken down.

The Lower Yard was filled with press, security forces and the families of officials, all reported to be waiting curiously, while on Dame Street and Parliament Street the crowd increased in size as time wore on, and ‘with tense vision the people watched the movement of troops, officials, and vehicles coming and going … There was a general air of breaking up about the place’ according to a reporter from the Irish Independent, whose impression of events was in the newspaper the following day.

The reporter recorded at 12 midday the arrival of William Evelyn Wylie the forty-two-year-old Dublin born Judge who was Law Advisor to the government of Ireland in Dublin Castle, since 1919. He was well known as the Crown prosecutor at the military tribunals after the 1916 Rising. The Provisional Government arrived at approximately 1.30pm in three cars followed by a horse drawn jarvey through the gate at Palace Street before turning right into the expanse of the Lower Yard of the Castle. The newspaper reporters detailed the events as they happened in a word picture for their readers. Michael Collins and Eoin MacNeill were in the first car, in the second were Éamonn Duggan and W.T. Cosgrave with the remaining members of the Provisional Government in the third car.

As they entered the Privy Council building, the pressmen recorded that Collins was followed into the building by what they called ‘other staff’, these would have included: Patrick Hogan, Fionán Lynch, Joe McGrath, Kevin O’Higgins and what the Irish Independent dubbed ‘lady typists.’ We know one of those who was there that day was Sinéad Mason.

Clare man, Sean Clancy, then twenty-one years old, was also present that day. He had been active during the War of Independence and had served in the Irish Republican Army’s Dublin Brigade. He accepted the terms of the Treaty and would enjoy a long career in the Irish Defence Forces rising to the rank of lieutenant-colonel. His memory of the events of the day were recorded by Seán O’Mórdha in 2000 in an interview conducted for the first episode of the television documentary Seven Ages ‘The birth of the new Irish state’. At the time of his death, aged 105 in 2006, Clancy was the longest living recipient of a military service pension for his role in the War of Independence. His memory of an event on the day was not recorded in the newspapers. According to Clancy a British official commented on Collins being seven minutes late and Collins was heard to reply: ‘Blast you, sure you people are here for seven centuries and what bloody difference does seven minutes make now.’

Dublin Castle during the War of Independence was an intense, claustrophobic environment. Some limited social and musical events did take place there during that time, mainly for the benefit of its overwhelmingly British residents. Any potential perception of insensitivity in holding such events was outweighed by the need to let off some steam in the course of a lengthy confinement. Of course, social events also ‘enabled the remnants of Dublin society to invade the Castle precincts in the afternoon and while away the official hours by jazz or foxtrot’ as George Chester Duggan recalled. Duggan was part of Dublin Castle’s administration during the War of Independence. He had entered the British Civil Service in 1908, now in his mid-thirties, he was in his second term in the Chief Secretary’s Office in Dublin Castle. He wrote his reminisces using the nom de plume ‘Periscope’. His account from inside the Castle was published as ‘The last days of Dublin Castle’ in Blackwoods Magazine in August 1922.

According to British civil servant Mark Sturgis, (Sir Mark Beresford Russell Grant Sturgis), who was called over to Ireland to act as Private Secretary to Sir John Anderson, Joint Under Secretary and senior representative of HM Treasury in Ireland:

In January 1921 there was much consternation when F Company of the auxiliaries tried to take advantage of the absence of some senior officers by staging a New Year’s Eve ball in St Patrick’s Hall and were found selling tickets for the event.

Sturgis had been seconded to Dublin in the summer of 1920. He recorded that most of those who worked and now lived in the Castle had to adhere to rigorous security checks. Sturgis became the chronicler of events in Ireland from the vantage point of the Castle through five volumes of his diaries that he kept between July 1920 and January 1922. A selection of these diaries were edited by Michael Hopkinson and published as The Last Days of Dublin Castle: the Mark Sturgis Diaries, Irish Academic Press, 1999. In one entry he notes:

yet these beauties can almost without by your leave or with your leave import a pack of women of whom nobody with the possible exception of themselves knows anything at all. Interesting to see when I get back to-morrow whether the Shinns have got in disguised as buxom wenches or whether failing this the whole place has been fired up by the festive ex-officers themselves.

Another account of entertainment from inside the Castle walls came from a member of the Dublin Castle Administration, short-hand typist Lily Mernin, in her witness statement for the Bureau of Military History

The Auxiliaries organised smoking concerts and whist drives in the Lower Castle Yard. I was encouraged by Frank Saurin a member of the Intelligence Squad, to give all the assistance I could in the organisation of these whist drives for the sole purpose of getting to know the Auxiliaries and find out all I possibly could about them.

Some of the Auxiliaries saw their female visitors to the tram afterwards, only to be shadowed by IRA members seeking to identify them. Security in and around the Castle intensified as the conflict dragged on, but the IRA tried to exploit any vulnerabilities. As George Chester Duggan observed the photographic identification that was introduced to get in and out of the Castle. This was ‘admirably suited to London offices in wartime’ but in Ireland such documents were ‘a menace to those labelled in this way’ he blamed them for the death of at least one officer.

as one left the Castle one had a feeling of watchfulness. As I walked up Dame Street I have at times looked back with that—sub-conscious sense of being followed—and by whom? The life of a Civil Servant in London seemed humdrum when compared with this brooding sense of fatality, but I don’t suppose many English Civil Servants would have wished to exchange places.s.

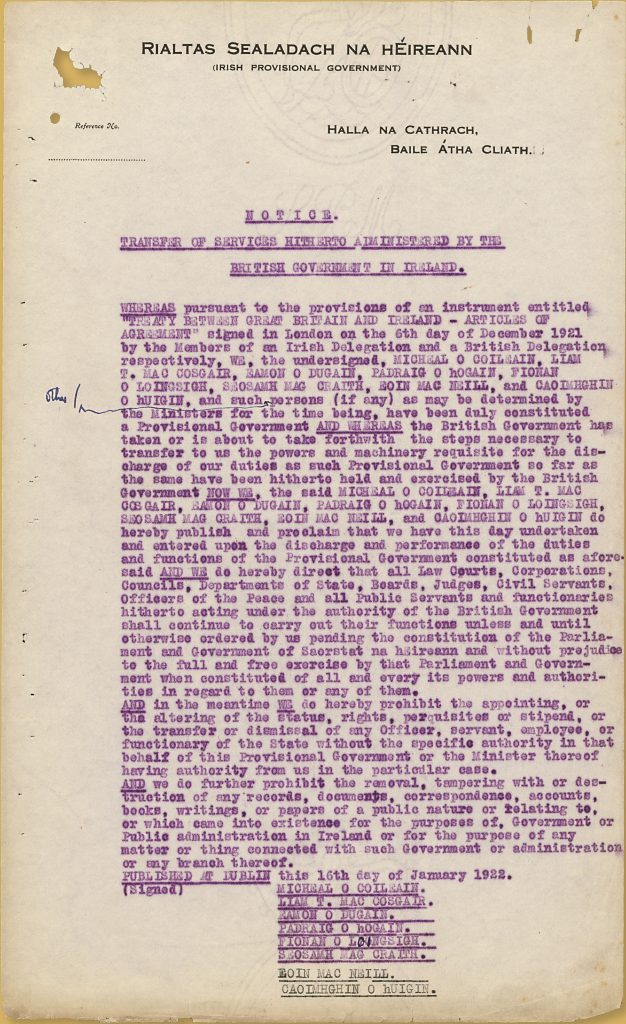

At 11am on the morning of 16 January 1922 Michael Collins, Chairman of the Provisional Government recorded the plan to go to Dublin Castle. This decision is recorded in the minutes of a meeting, the paper has the heading of Rialtas Sealadach na hÉireann (Provisional Government of Ireland) now held in the National Archives of Ireland (TSCH/1/1/1). The meeting held at the Mansion House was attended and chaired by Michael Collins with W.T. Cosgrave, Éamonn Duggan, Patrick Hogan, Fionán Lynch. Joseph MacGrath. Eoin MacNeill and Kevin O’Higgins. Under the title: Arrangements for taking over Functions:‘arrangements were made to visit Dublin Castle at 1.40 p.m. in the after- noon for the purpose of taking over the various Departments of State’.

British Civil Servant George Chester Duggan later recounted this meeting in ‘The last days of Dublin Castle’ in Blackwoods Magazine in August 1922:

…a motley assemblage: some in tweed caps and unpolished boots; others with the beards of yester-eve still fresh on their chins, others with long lanky hair, collars and ties au peintre. Mr Collins himself was first in the door, and though the red carpet had in its time been laid down in the hall and up the stairway for many strange personages, yet surely this was the strangest scene of all it had yet beheld..

Ascending the stairs to the Privy Chamber they were greeted by Belfast born, James MacMahon, Under Secretary for Ireland and member of the Privy Council. He assured Collins he was welcome, Collins passed him, and without breaking stride replied: ‘Like hell we are.’

No flag was flown over the Castle, even after the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland Edmund Bernard FitzAlan-Howard arrived, a few minutes after the Provisional Government. He was greeted with cheers, which the Irish Independent described as more muted than those that had greeted the earlier arrivals. They had all made their way to the Privy Council Chamber, which was located over the gate between the Lower and Upper Yard, the windows of which conveniently provided a good view for the spectators within the Castle yards. The Cork Examiner, gave their readers an account of what the Chamber looked like:

The simple stateliness of the Chamber with its two great brass chandeliers, pendant over the red cloth-covered table which occupies the centre of the room, must have impressed the new Ministers. The proceedings were private, but it is understood that the Viceroy, as representative of the King, received them as His Majesty would receive new Ministers..

The room and the seating arrangements were clearly visible from the yard. FitzAlan was observed standing at the fireplace at the end. Journalists recorded how ‘through the windows Mr Collins could be seen smiling and looking absolutely self-possessed as he met the Viceroy.’ The members of the provisional government were introduced to their counterparts in the Castle administration. Sir Henry Robinson, who had been Vice President of the local government board of Ireland since 1898 was called to attend, in his memoirs he recounted:

On the day fixed for the surrender of the Government to Sinn Féin I received a telephone message to attend at the Council to be introduced to the victors … I did not join the glad throng, and went out into the corridor, where I was followed by Mr Justice Wylie, who I suspect found it anything but pleasant to be confronted with the new Ministers, most of whom he had prosecuted when Solicitor-General for various offences in connection with the rebellion. Inside the Privy Council Chamber Lord FitzAlan was making the formal abdication of the Irish Government to Michael Collins, and having got through with this he left by the door to the State apartments, and so avoided meeting his trusty and well-beloved civil servants with a sauve qui peut [‘every man for himself’], which was the only advice he would have had to offer them. After his departure … James MacMahon then proceeded to call in all the heads of departments to make them known to their new chiefs, and I, being senior in the service, was called in first and was marched round and introduced to each one in turn, just as a newly sworn privy councillor is presented to the other members of the Council. What struck me most was the extreme youth of most of the new Ministers; they seemed scarcely out of their teens, and all looked pale and anxious. No doubt they had been through a period of terrible anxiety, and they certainly looked gloomy and overpowered with the consciousness of responsibility for the future government of the country.

Sir Henry Robinson Memories: wise and otherwise, (London, 1923) 324-26

Many of the clerical staff had been released to watch the proceedings and some were even taking photographs themselves; there was apparently ‘a good deal of gaiety and fraternisation’ in the Upper Yard, according to a Freeman’s Journal reporter.

The Official British statement reported in newspapers the following day wished the new Provisional Government ‘every success’ and expressed ‘the earnest hope that under their auspices the ideal of a happy, free and prosperous Ireland would be attained.’

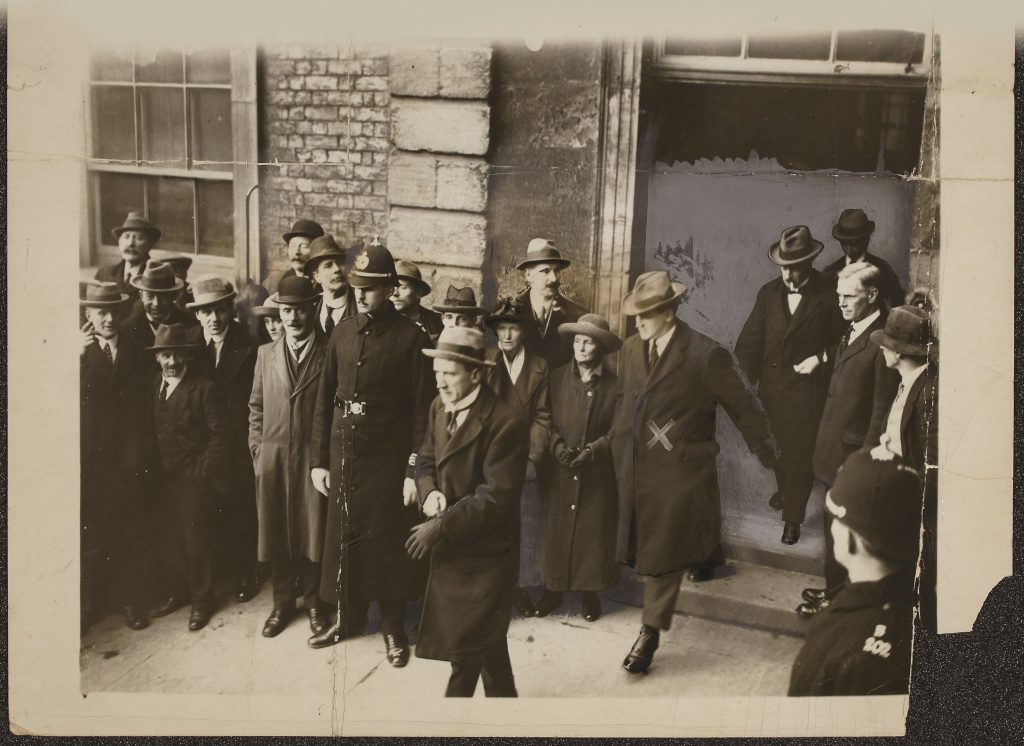

The meeting in the Privy Council Chamber had lasted less than one hour. The members of the British Administration began to leave at 2.10pm, followed by members of the new Provisional Government who departed at around 2.30pm. The Irish Independent reporting on the 17 January 1922 identified in the crowd a number of Castle officials and several American visitors (that remained unidentified).

The unidentified women in this image seen on the left as Kevin O’Higgins, Michael Collins and Éamonn Duggan emerge from Dublin Castle after their meeting, are described ‘Lady Typists’ in the Pathé News footage, but they could be employees of the British Administration, their glum expressions perhaps allude to an uncertainty surrounding their future employment.

The members of the Provisional Government made their way back to the Mansion House. Business carried on at Dublin Castle, including the removing of stores, bedding and documents. A Freeman’s Journal reporter had noted that during the meeting in the Privy Council Chamber a military lorry was outside the Privy Council suite, in the Upper Yard just west of the Bermingham tower and was being loaded with ‘an immense number of volumes, some of them, at any rate, of substantial antiquity’. The journalist pondered: ‘It would be interesting to know if they were amongst the records styled under the old regime “Confidential”.

The Provisional Government officially reconvened at 4pm and agreed a brief statement on what had just happened. ‘The members of the Irish Provisional Government received the surrender of Dublin Castle at 1.45pm today. This is now in the hands of the Irish Nation.’

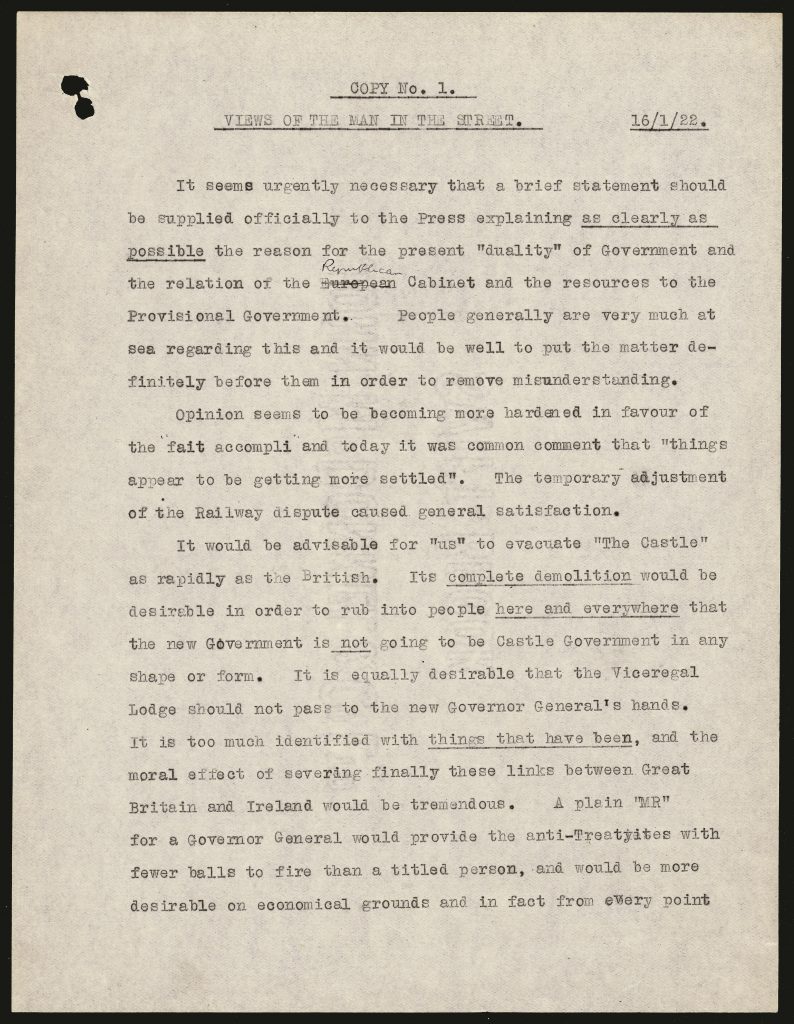

On 16 January 1922 as the evening drew in, readers of the Evening Hearld read a suggestion that ‘The Provisional Government will make a great mistake if it does not level Dublin Castle to the ground’.

City Hall became the home of the Provisional Government, despite an unsuccessful motion being tabled a few days later by Sinn Féin Councillor and TD Kathleen Clarke (née Daly ) (who had opposed the Treaty), demanding that the Provisional Government ‘remove themselves to where they had plenty of room – namely the Castle that had been handed over to them. ’Kathleen was elected as TD for Dublin in May 1921. She voted against the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland. She had been arrested and held in Ship Street Barracks at Dublin Castle in the aftermath of the 1916 Rising. Kathleen Clarke was a founder member of Cumann na mBan. Her husband Tom Clarke and her brother Edward (Ned) Daly had been executed for their part in the rebellion at Easter 1916.

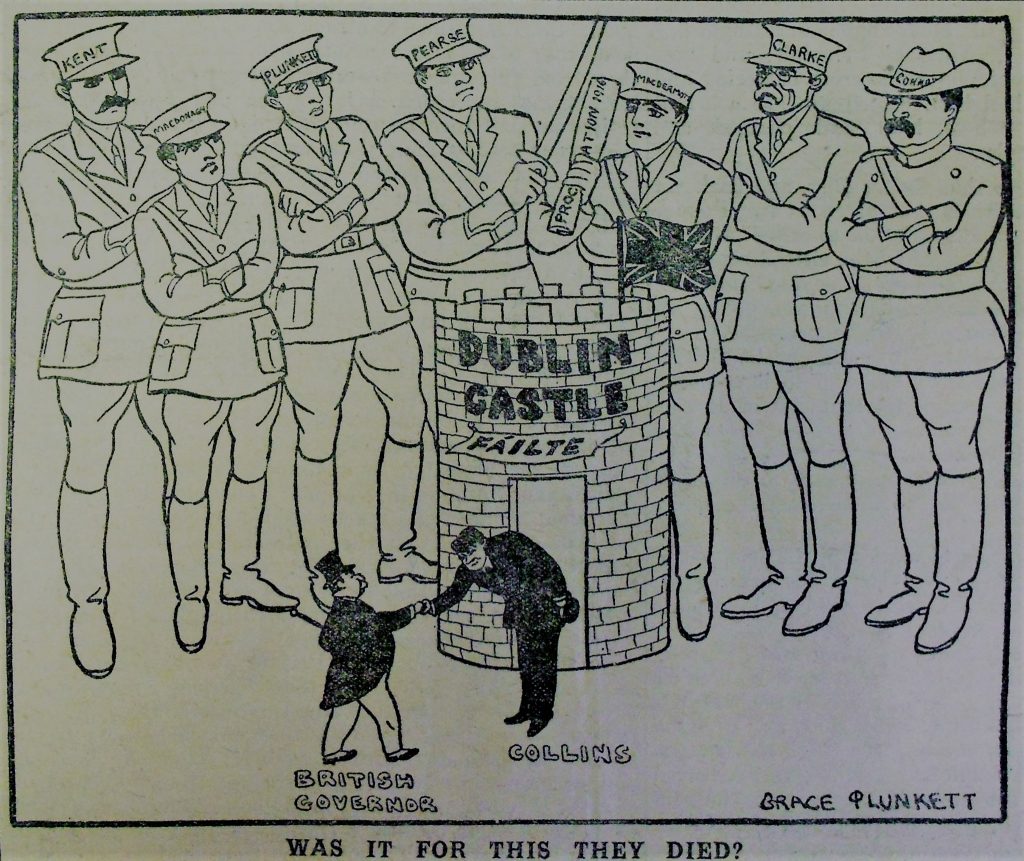

Another widow of a 1916 Leader, executed for his part in the 1916 Rising Grace Plunkett (née Gifford), Artist, Cartoonist and Political Commentator recorded her view of events in a customary cartoon. She had married Joseph Plunkett the night before he was executed.

This cartoon, published in April 1922, depicts Collins bowing before the ‘British Governor’ while the ghosts of the executed leaders of the Easter Rising look on. The caption poses the rhetorical question: ‘Was it for this they died?’ The implication is of a surrender by Collins to the British; the opposite of how Collins and supporters of the Treaty depicted the event.

Something of the wider political context of the events of January 1922 were covered internationally the editorial of the New York Times reported on 17 January 1922:

Now the Castle is in Irish hands. Lord FitzAlan turns the strong place over to “Mickey” Collins. The building which meant so long English domination now stands for Irish triumph. Its possession by the Free State is one more powerful advantage of the Provisional Government against the Irish irreconcilables. Will de Valera presently be found ranting in the old way against “Castle” influence after Michael Collins has taken up his official residence there? Not unless Irish humor is extinct. The steps already taken cannot be retraced. The abhorred Castle has now become Irish, and it is for Irishmen to make of it, if they can, the source and centre of the free and stable Government.

A Manchester Guardian reporter based in Dublin wrote in the newspaper on 17 January 1922: ‘I hope no Irish Government will ever make it a seat of authority’, for, both ‘as terrible legend’ and due to its more recent uses, Dublin Castle ‘would be a fatal home for any Government in this country’.

Further press commentary has been analysed by Dr Elspeth Payne and some of her work on the British newspaper coverage is included here.

If the British press knew that the ‘three or four lady typists’ were in the cars leaving the Lower Castle Yard at 2.30 pm with the Irish provisional government on 16 January 1922, they did not care to share this with their readers.

The five words that conveyed the presence of these unnamed women in the Drogheda Independent, Irish Weekly and Ulster Examiner, and Ulster Herald did not make it into even the more detailed reports printed in the British national and local newspapers.

This is not surprising. Although some of the titles listed all the members of the Provisional Government involved in proceedings that day by name, others simply referred to the group as ‘Mr. Michael Collins and seven other typical Southern Irishmen’.

Indeed, the absence of the ‘lady typists’ is certainly not indicative of a lack of interest in events at Dublin Castle that day. Although no journalists were admitted to the ceremony, the British press carried detailed accounts of the ‘historic’ scenes inside and outside Dublin Castle, photographs, and official statements and telegrams.

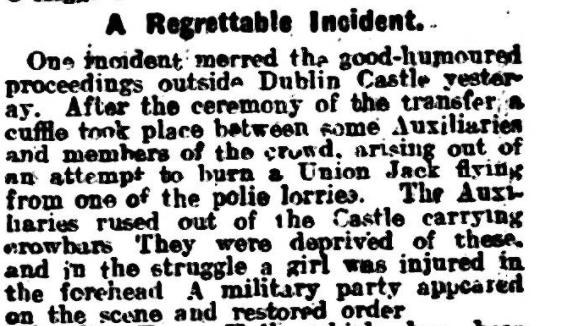

Women can be found on the periphery of this content. Keen to catch a glimpse of the new Irish government and be part of the momentous day, they appear in the pictures printed of the crowds lining the street. Some, but not all, reports of the ‘scuffle’ over a union jack mention a young girl who was injured. A visit by Michael Collins to his fiancé, Kitty Kiernan, in County Longford was noted by the tabloid Daily Mail.

Although such references should not be overstated – the coverage focused on the male protagonists – there was not a complete erasure of women from Irish politics and life in 1922. The British newspapers were, for example, aware that female as well as male prisoners were released under the general amnesty that month. But just as the press was captivated more by Michael Collins than his seven colleagues, it was typically Constance de Markievicz and Mary MacSwiney – the so-called republican ‘die hard’ ‘hysterical women’ – who secured column inches.

Mná100 would like to thank Dr Kate O’Malley, Dr John Gibney, Dr Valeria Cavalli and Ruth Hegarty of the Royal Irish Academy. Dr Elspeth Payne from Trinity College Dublin and Sean Gannon from Limerick City and County Council for their assistance and contributions.