Art as Commemoration

For centuries portraiture has been used as a form of commemoration. During the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023, a number of portraits of those involved in the Irish Revolution have been commissioned.

Mná100’s Dr Sinéad McCoole met with artist Emma Stroude to discuss her process of producing commissioned portraits.

Artist Emma Stroude completed her studies in London at Chelsea College of Art and Design and The Slade School of Art. She moved to Ireland in 1996 and studied at National College of Art and Design.

As she describes herself, she is primarily a painter. Stroude’s current practice, she says, is ‘underpinned by a dedication to life-drawing, which has a strong influence on her work.’

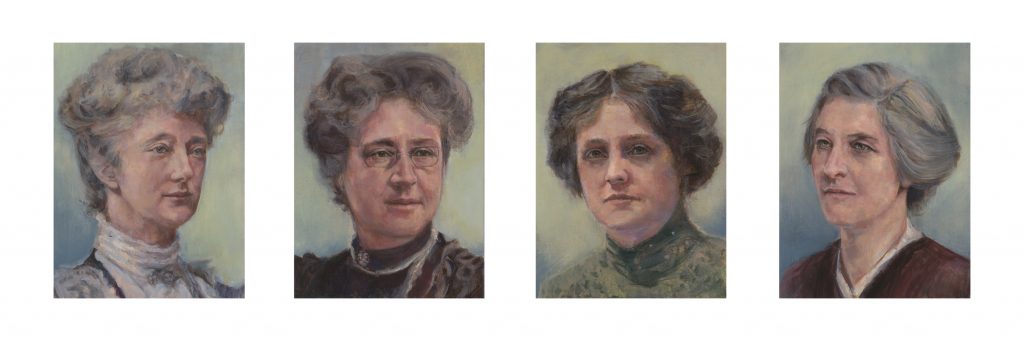

In 2022, as part of the centenary of the Irish Senate, a series of portraits of the first four women senators elected, were commissioned by the Office of Public Works to hang in the Houses of the Oireachtas.

Stroude was selected to undertake the task to create contemporary images of these historic women – Alice Stopford Green (1847-1929) Ellen Cuffe, Countess of Desart (1857-1933), Jennie Wyse Power (1858-1941) and Eileen Costello (1870-1962).

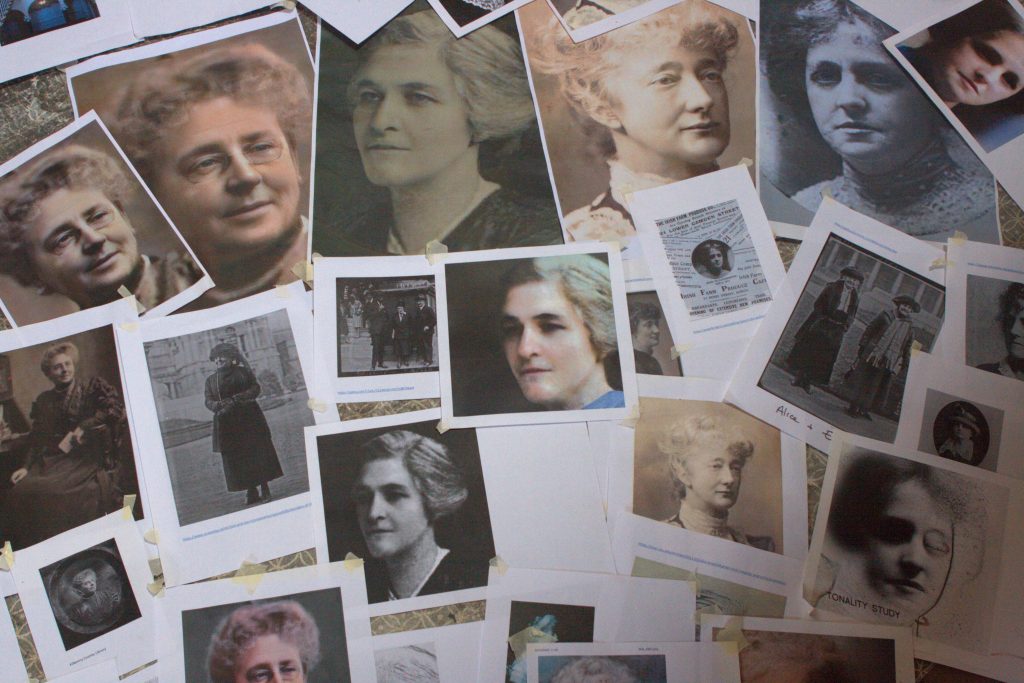

Stroude began her research with the assistance of Áine McCarthy and together they created a written and pictorial over-view of the lives of these women.

In late 2022 I was commissioned by the Office of Public Works to create portraits of the first four women elected to the first Seanad Éireann in 1922. The paintings are now part of the State Collection at Leinster House and hang at the top of the Seanad stairs.

The making of the portraits was a rewarding learning experience for me. Prior to the commission I was unfamiliar with Alice Stopford Green, Ellen Cuffe (Countess of Desart), Jennie Wyse Power and Eileen Costello. Through my research I discovered four diversely different women who are all equally interesting and who all contributed significantly to the Ireland we live in today.

Alice Stopford Green was a historian, a nationalist writer, a member of Cumann na Saoirse and a close confident to Michael Collins. To find out more, visit her Dictionary of Irish Biography entry here. To find out the story of her commission of the Senate Casket visit here.

Ellen Cuffe, Countess of Desart, was a philanthropist and a humanitarian. Stroude discovered that she was well known in Kilkenny as she put in place the hospital Aut Even, and the theatre, factories and businesses that provided jobs and income for its people. To find out more, a link to her Dictionary of Irish Biography entry is here.

Jennie Wyse Power was a leading suffragist, a founding member of Cumann na mBan and later Cumann na Saoirse. Stroude found out by her reading that she was politically active from her earliest years, she was active in the period of the Land War, and it was at her shop on Henry St. that the Proclamation was signed before being brought to the GPO. She was also Vice President of Sinn Féin. To find out more, read her Dictionary of Irish Biography entry here.

Eileen Costello was also a member of Cumann na Saoirse. She was a collector of Irish songs and music for Irish Schools and Gaelic League classes. By reading the Dáil Debates, available online, Stroude found that she had a strong voice in the Seanad, promoting and pushing for equality for women. To find out more, read her Dictionary of Irish Biography entry here.

The Commission

Dr Sinéad McCoole visited Stroude in her Sligo studio to find out more about her process during a commission such as this one. During the visit she allows Dr McCoole to look through her notebooks. This original source material is key to finding the first-hand voice of the artist.

The Notebook

From this notebook it was clear that Emma Stroude had a command of the subjects from the start.

While she was working on this commission, she was writing in her notebook. On one of the first pages Stroude had written the quote:

‘Short-term thinking always tries to avoid the genuine need to suffer the opposites long enough for a third way to emerge.’

Michael Meade.

Stroude was listening to Michael Meade’s podcast at the time. Listening to someone talking about issues as they affect society, citizenship, and justice. It is possible to understand the link to the creation of the images of these women, as senators. Although long since deceased, this understanding of their work and motivation would be essential to understand what they did and why they worked for others.

Stroude discovered that these women were businesswomen, poor law guardians, county and city councillors, teachers, mentors, activists, mothers, wives, sisters and daughters.

‘They lived full lives working for others, their selection for the senate was because of their body of work, the fact of their standing in their respective communities. All of these women were in older age when they were senators.’

The notebook was full of insights into the mind of the artist as Stroude began her task.

Stroude wrote a note to herself at the time that she was starting this commission: learn to sit with uncertainty. The emotion of the creative process is contained in the notebook as UNCERTAINTY is capitalised. There is a tension contained in here, to get it right for the client, the viewer, the place, but still for the artist to feel that they have fulfilled the need of their own practice, to stay true to their own art form.

This notebook is a step-by-step guide.

‘Notes on what to do next. The search was on for better quality photographs.’

Stroude did not have living sitters or even someone to talk to who knew these women during their lifetimes, no-one to convey their stories, just old photos sometimes in a book, not even original images. They discuss the lack of source material. How much material might have been lost in raids and fires as these women were living through times of war.

Stroude was working from poor quality newspaper images and a few photographs which were mostly third or fourth generation copies. Stroude explained that early in the process she made the decision to use images of the women at the age they were when they were senators and about her search for those images.

You can see from this notebook, a woman at work, the artist, the maker with the practical needs, the setup, the new requirements of the studio space. The time, effort, cost, planning that no one sees when they see brush strokes on canvas.

It is not to be mistaken as a notebook detailing life administration but a record of the work of an artist. Even when Stroude makes a note to self to finish reading the books. ‘Have it all done by tomorrow pm so I can paint all day Thursday and Friday.’

Stroude had a short lead in time to the centenary date. Does a short time to a fixed centenary help the process? Stroude says it drove her. This echoes to another artist found on Mná100: Estella Solomon.

The decision of the shape of the works comes onto the pages of this book. In the notebook Stroude questions whether they should be square or portrait and what size they should be. She decides on a portrait format 40cm x 30cm as having the best potential impact in the space.

She recognised early on that there needed to be luminosity in each painting.

Then it was time to see the location where the painting would be hung. Stroude travelled to Dublin to visit the proposed location for the paintings in the Seanad and to discuss the project with Head of Art Management at the Office of Public Works, Jacquie Moore. Stroude noted Jacquie’s suggestion of ‘a contemporary frame with a nod to tradition’. She logged measurements of the wall space and ceiling height. She noted the width between the wall and the stairwell edge which would lead to a closer, more intimate viewing space.

Following her visit to the Houses of the Oireachtas, Stroude made her way to the National Gallery of Ireland located nearby, she had written about her visit in her work diary:

‘The National Gallery makes my heart sing. I walked around in it today. Mind blown. Always new discoveries and old friends. Estella Solomons – girl with a red tie – YES.’ Caravaggio spray paint before there was spray paint.’ Faces. Faces. Faces. Velasquez ‘Maid with supper’ 400 years old, … still a face that rings true today.’

She returned to her work in the studio with reference points from the past and brought them into her work in the present. She began her works on canvas with paint and her images emerge.

The following series of pictures illustrates the gradual build-up of paint as the portraits begin to reveal themselves.

Stage 1:

Stage 2:

Stage 3:

Stage 4:

Emma Stroude studio Co Sligo. Photography by Kate Nevin

Emma Stroude believes that it is so important to the understanding of the creative process, the need to clear the space to create, to just be with the paint and the canvas, to do the work.

Stroude’s studio is nestled in the foothills of Ben Bulben, the majestic flat-topped mountain in the Dartry Mountain range. W.B. Yeats wrote Under Ben Bulben, in the final months of his life, in 1938, and the closing words of the poem were later carved in stone on his headstone in the churchyard of nearby Drumcliffe.

This poem speaks to the ancient sagas and the oral history of Sligo. So much of the place in which Stroude lives and works has echoes of the writers, poets, and painters of old.

Stroude is active in the artistic community of this area, the poem’s lines seem present as they sit down to talk in her studio, a stove fire illuminates the old walls as it would have done 100 years ago.

….Poet and sculptor do the work

Nor let the modish painter shirk

What his great forefathers did,

Bring the soul of man to God,

Make him fill the cradles right.

W.B Yeats

The Maud Series

Stroude’s interest in Irish women began before the Decade of Centenaries 1912-1923, when she began to read Irish history and was drawn to images of Maud Gonne MacBride (1866-1953).

Stroude began her exploration of Irish women with a series of images of Maud Gonne, the woman who is known to many as W.B. Yeats’ muse. Later known as Madame Gonne MacBride, she married John MacBride, executed for his part in the 1916 Rising. For Stroude, her interest in Gonne was as a strong woman,. To read more about her, read her Dictionary of Irish Biography entry here.

When Stroude began making those drawings of Maud over 10 years ago, it was not, she says, ‘an interest in Irish History that led her to Maud, but that Maud led her to an interest in Irish History.’ As Stroude described: ‘My fascination’ which began ‘because of a deep-seated need in me – a time in which I needed to develop her qualities of courage, determination, fearlessness, and persistence. I think this is what drew me to her. It was a time that I left a full-time job to return to my original ambition of becoming a professional artist and for this I needed to build resilience and a strong will.’

Some of the drawings are now stored in the studio.

Stroude describes:

‘The challenge in Maud’s gaze is remarkable. She invites you to step up to the mark, to put all in and not to bury your head or shy away from facing the difficult path forwards. When I face Maud, I feel that it is me who is being scrutinised, my morals, my actions, my intentions, and I do not want to fall short. Drawing her over and over again allowed me to focus on my own determination and persistence in the act of trying to create work of weight and substance and finding that elusive presence in a portrait.’

‘The more I drew Maud, the more I felt the need to begin reading about her and finding out about who she was. Her attitude to conquering her fears by facing them directly inspired me to do the same. The challenges she met in her life and the risks she had to take were so much greater than anything that I was facing that it put my own fears in perspective and gave me the courage to plough ahead with my own chosen path.’

Those who know the extensive photographic record of Maud Gonne from her days as a celebrity speaker to stately old woman, will see the clarity of the likenesses that Stroude has captured.

Stroude discusses Maud’s legacy as Madame MacBride lived on into old age, protesting injustice until the end of her long life. The works are in the main in charcoal, and unlike other works many remain with her, still in studio, and she has gifted many ‘Mauds’ to friends and supporters.

“Of course I did not realise any of this at the time. I always find with my work that it takes about 3 years’ distance for me to be able to look back and see the truth of what I was doing at the time. In 2012 I was fascinated by her; I needed a focus to develop my portraiture skills and she had such an interesting face and personal history that working on her became a bit of an obsession for a while. Now I can see the significance much more clearly and gratefully it marked the beginning of a much wider interest in people who played key roles in shaping Ireland and the experiences of the people who live here today.”

It is fitting now that Stroude paints the first four female Senators who carried on with similar determination to Maud Gonne.

A commemorative art piece is not just commissioned at the date of a centenary. In 1924 Senator Alice Stopford Green commissioned a special piece from artist and designer Mia Cranwill. The ideal choice; as Miss Cranwill had studied Irish history and mythology, according to her Dictionary of Irish Biography entry, and worked in her own Celtic style. The Senate Casket, which was presented in 1924, to hold a scroll with the names of the senators, was to rest on a stand of Irish yew, but it also could be carried. It was based on ancient religious shrines and the Gallarus Oratory in County Kerry. Its design was based on surviving Irish artefacts and manuscripts from what was described, by the senator at the presentation, as ‘Old Ireland.’ She told her assembled audience that if they wanted ‘to revive’ an Irish nation ‘we must dig our roots back to the soil and be nourished by the ancient earth.’

During the celebration of the 100 years of the Seanad, the casket was displayed in the centre of Dáil Éireann where all the senators gathered around to give their speeches. When Stroude recalled seeing it, she said that artwork was a significant moment for Alice’s legacy.

Stroude’s work now can be seen in local public buildings, national and international locations. Stroude’s work will last as legacy of this time, but living on as a reflection of us now, not simply of times past but into the future.