Westmeath Women

Alice Ginnell, Kitty O’Doherty, Lizzie Leonard, Eileen McGrane

Where were these women when the Truce was declared, and what was their contribution to the campaign of independence?

Mná100.ie in partnership with County Westmeath’s Decade of Centenaries Historian-in-Residence Dr Paul Hughes focuses on a number of women from Westmeath and where they were 100 years ago when the Truce was declared. During the campaign for independence, these Westmeath women were among several from the county who made significant contributions locally, nationally and internationally.

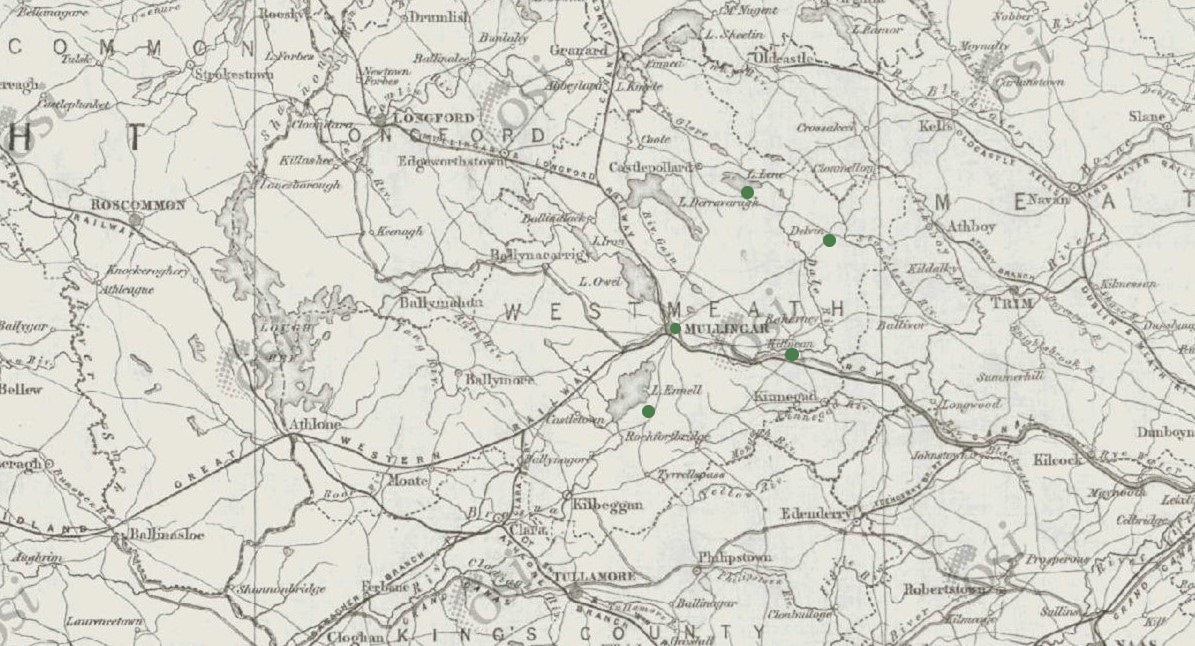

Dr Paul Hughes is currently working on a biography of the MP, agrarian radical and revolutionary Laurence Ginnell (1852-1923), which was the subject of his PhD at Queen’s University, Belfast. He has contributed articles to the Westmeath Examiner and Westmeath County Council’s commemorative blog on the role of women during the Decade of Centenaries. He has located new source material, giving first-hand accounts, and new understanding of the activities of women such as Kilbride’s Alice Ginnell (née King), wife of Laurence Ginnell, and Tyrrellspass native Kitty O’Doherty (née Gibbons), who were both involved in promoting Ireland’s right to self-determination abroad. He has also examined the Military Service Pension application of Delvin’s Elizabeth ‘Lizzie’ Leonard, who with her sisters Peg and Mary, ran a café in Mullingar which was a centre of republican activities before and during the Truce. His interview with Marika MacCarvill gives fresh and engaging insights into Killucan’s Eileen McGrane (Later Dr. Eileen MacCarvill), who was at the centre of Michael Collins’ intelligence network during the War of Independence.

Alice Ginnell

In July 1921 Alice Ginnell, was on her way to South America with her husband Laurence Ginnell to bring attention to Ireland’s right to self-determination and raise funds for the Irish cause.

Born Mary Alice King on 24 September 1882, the eldest daughter of James and Georgina (née O’Sullivan) King, she was the eldest of seven surviving daughters, Constance (b1883), Marcella (1885), Georgina (b1887), Kathleen (b1891), Mary (1892) and Madeline (born Magdalen, 1895), and a brother James, who died in infancy. Alice’s home was Kilbride House, Gaybrook, a nineteenth century farmhouse where her father was, according to Dr Hughes a ‘farmer of means’, who also established an auctioneering business. Alice would have been aware from an early age of local politics, as her father became Vice-Chairman of Westmeath County Council in 1899.

Alice was well educated. She attended boarding school at the Loreto Convent in Navan, County Meath. In the immediate years after her schooling she is unaccounted for and Dr Hughes has concluded from his research that she was probably on the continent, as a number of her sisters spent time there continuing their education or briefly working as governesses. How she came to know Barrister and United Irish League official Laurence Ginnell, and began a courtship, is unknown, but it is likely that she met the Delvin native through her father, a wealthy Catholic landowner, almost the same age as Ginnell, who was immersed in the politics of Westmeath.

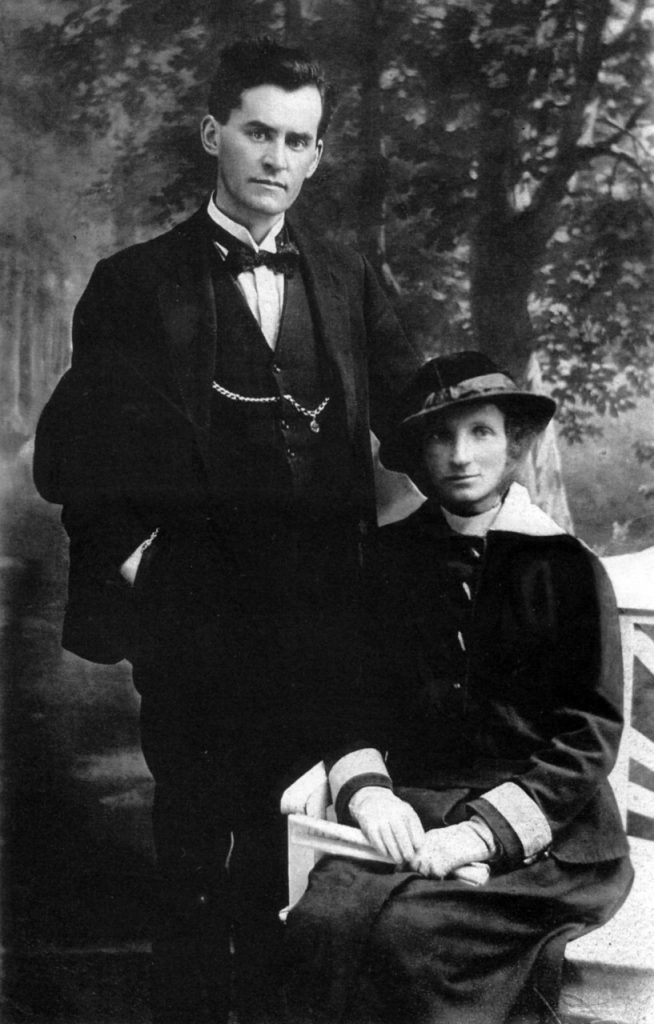

On 30 January 1902, at the age of nineteen, just sixteen months after leaving education, Alice married Laurence Ginnell, thirty years her senior, at the local church in Rochfortbridge, County Westmeath. She was his second wife (his first wife, Margaret Woulfe and their baby boy both died in June 1883).

The time of their marriage coincided with a busy time in Laurence Ginnell’s political life, and Alice was at his side during much of this period. In 1900, he stood as an Irish Parliamentary Party candidate in Mullingar, but was unsuccessful. His involvement with controversial work in the United Irish League’s headquarters meant that, in Alice’s own words, they had to go ‘on the run’ in June 1903 and stayed in France for a brief period. In 1906, Laurence became Member of Parliament for North Westmeath in Westminster, and the couple lived in London for much of the next eleven years. In late 1906, Laurence launched the ranch war against grazing interests in Ireland and pioneered the practice of political cattle-driving; during this period, his political activities led to a term of imprisonment. Alice returned home to her family during these times; on one occasion, Laurence was arrested in her father’s house at Kilbride.

Paul has uncovered from a diary in a private collection, that Alice Ginnell contributed columns to several newspapers during the 1910s, particularly the ‘London Gossip’ column published in the Mullingar newspaper, the Midland Reporter and Westmeath Nationalist.

Between 1909 and 1916, she worked as a translator, among other duties, at a colonial brokerage firm in London: Lockie, Pemberton and Co. She left the company suddenly, but amicably, in May 1916, after her husband’s connections to and public defence of the Easter Rising in the House of Commons brought the couple a degree of notoriety. Alice toured the prisons under a false name collecting and giving information to the prisoners, and worked closely with Art O’Brien on the Irish National Relief Fund. She also agitated, unsuccessfully, to drum up support for the rebels and their families among members of London’s Irish Literary Society.

Alice was a member of Cumann na mBan, and after the Rising was active in reorganising that organisation as well as Sinn Féin. She was a part of the League of Women Delegates to the All-Ireland Conference. She became involved in the election of Sinn Féin candidates, when she was chosen to go Oxford to approach Count Plunkett to stand in the 1917 by-election in North Roscommon. Later when her husband stood as a Sinn Féin candidate in 1918, in her own words, in her Bureau of Military History witness statement, her role in the election campaign in Westmeath, was the first time a ‘woman was an election agent in the British Isles.’

In 1920, Alice stood unsuccessfully in the Dublin municipal elections, in the Pembroke ward, where William Beckett, a unionist candidate and father of the novelist and playwright Samuel Beckett, was among those elected. Later that year the couple were sent to the United States, posing as Mr and Mrs Jones. Laurence Ginnell was established as a Dáil consul in Chicago. As Dr Hughes describes, they were well placed ‘in the American Midwest – the wide, pastoral expanse known to Americans as “the nation’s breadbasket”’. It was an ideal location to raise funds for Dáil Éireann and to contribute to the working of the Department of Finance, raising Dáil loans. In December 1920, the Ginnells were in Washington, D.C., when the hearing of the American Commission for Conditions in Ireland took place, Laurence testified. For context see: Centenary Moments: Toward America.

Joe Begley, Mrs. Ginnell and Mr. Laurence Ginnell, IE/MA/AL/IMG/224, Brother Allen Collection, Military Archives. Courtesy of the Bureau of Military Archives, Ireland.

Laurence and Alice were reassigned to South America in the summer of 1921. According to Alice, the couple studied Spanish as they waited to obtain a diplomat’s passport. Laurence Ginnell was to act as ‘Envoy Extraordinary to the Government and Peoples of South America.’

Alice was not happy to be heading to South America, as she had concerns for her husband’s health. She later recalled that Harry Boland was aware that she did not want to go, though she thought she had concealed it. In her Bureau of Military History statement, she said that before she departed she did make it clear that she wanted Eamon de Valera told directly that she did not like going to South America.

While they were on the ship a wire came to inform them that the Truce had been signed, and negotiations had begun. As Alice later recalled, ‘Had the news come before we left, we would have been headed for home and not for South America.’ The couple remained in Argentina until April 1922, with Alice and Laurence joining the likes of Éamon and Anita Bulfin as part of a formidable team pressing Irish republican interests in Buenos Aires.

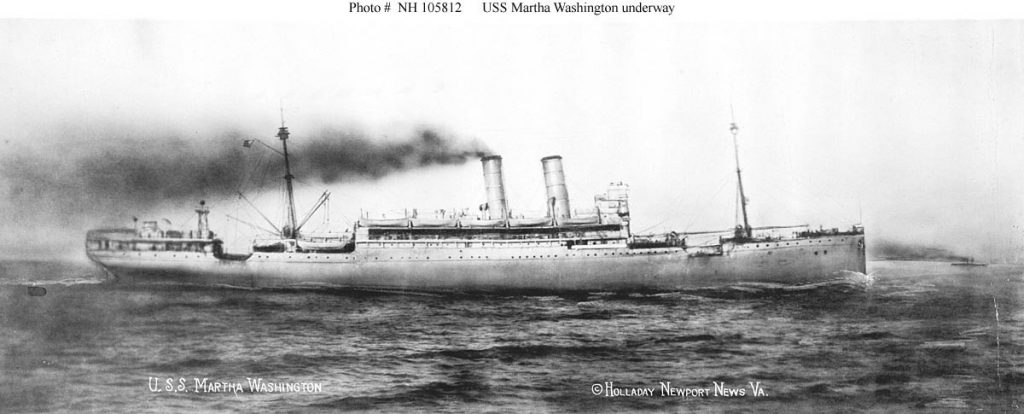

Dr Hughes has gained access to a private archive in Mullingar, County Westmeath, including a collection of letters written from the S.S. Martha Washington.

On the 14 July 1921, this letter was sent to the King family home, Kilbride House, Gaybrook, Mullingar, County Westmeath (text in square brackets comprises annotations by Dr Hughes):

Dearest Everyone,

We have just passed or are passing the Equator. It is very close & oppressive, but not so oppressive as one would expect. The journey has been lovely so far. Not a day that we could not sit out and look at the waves. We may get into Rio de Janeiro in two days where this will be posted. We left New York on July 3rd. Harry, Sean Nunan, Joe Begley (up from Washington for the Dempsey-Carpentier [boxing] match) & Liam Pedlar saw us off. Isn’t it funny that we were on the water this time twelve months too? The officers on this boat are extremely courteous. The most interesting people on board are the ex-President of Bolivia, Don [José Gutiérrez] Guerra, overthrown in a revolution last year & exiled, with his fortune taken. He is now representing a big American Bank. We have the son of a millionaire, two students from Notre Dame University (where the Castellini boys [of Ohio] are), spending their vacation seeing the world. In other vacations they went to India, China, Japan, etc. We have a lady Christian Scientist, who has been sick the whole journey. The companion of the ex-President is Wm O’Malley, the first officer is Mr Ryan & and the telephone operator asked me if I knew Cork.

There was just a hint that we might get a wireless to return to vote peace or war. So I keep wondering, but am quite ready to take things as they come.

––––––––––––

Crossing the Equator is a great event in naval life. The evening before, “Neptune’s Messenger” came on board to announce the coming of Neptune. At lunch Neptune himself, the Queen, the Royal scribe, the Royal barber, the Royal Doctor (the ex-President), the Royal nurse and the Royal police (all passengers dressed up) and the Royal Court came into the dining room, and called those who were to be initiated to appear at the Royal Court – one end of the deck.

––––––––––––

We all proceeded to the Court to be tried and sentenced for various crimes, the men for playing cards, smoking or not smoking anything & the women for playing the piano, for “vamping” … The men were sentenced to be shaved by the Royal barber & then thrown into the swimming pool. It was very nice, nothing vulgar. L[aurence] was accused of “being a gentleman” & was asked to explain why. I was accused of vamping with the Royal barber (who was her husband). I hope to get a whole lot of home news. Best love to you all from Alice.

In a postscript she added: Did Papa get the “Ideal Scrap Book”?

Kitty O’Doherty

At the time of the Truce Kitty O’Doherty was, as Dr Hughes states, ‘over 1,200km east of Chicago in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania’.

Katherine ‘Kitty’ Gibbons was one of seven children of Edward Gibbons, a sergeant in the Royal Irish Constabulary in Tyrrellpass and later in Fore and Collinstown, and his wife Anne (née Crossan) whom he had met while stationed in Meath.

In his research, Dr Hughes has connected Alice King and Kitty O’Doherty, both of whom were educated by the Loreto sisters in Navan, County Meath, with Kitty a year ahead of Alice. As Hughes explains, ‘both girls left the school with honours in several languages, qualifications which stood to them in their later careers.’ These interconnections speak to a network of contacts and friendships of what was known at the time as ‘the movement.’ Dr Hughes has discovered that after school in Navan, Kitty spent time in England and Germany, before training to be a teacher in Belfast. Her sisters Maria, Anne and Rose were also trained as national school teachers. Kitty moved to Dublin to take up a teaching post. There she became involved in the Gaelic League. In the summer of 1911 she married Seamus O’Doherty, who in Hughes’ description was ‘a travelling representative of Gill publishing house by day, and by night, a leading member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood.’

She was also at the centre of the events of those years, as her son Kevin later recalled in his memoir, My Parents and Other Rebels, that she was always sympathetic to the low-paid and disenfranchised. She had assisted Constance de Markievicz in her soup kitchen in Liberty Hall during the Labour Strike, 1913. She joined Cumann na mBan two months after its formation and was a member of the Ard Craobh branch. In her Bureau of Military History account she detailed her involvement for the preparation and planning for the Rising. Their home at 32 Connaught Street was watched as it was a well-known centre of activities. In her account, she described how in the aftermath her husband became Acting Head of the Supreme Council of the Provisional Government of the Republic.

Kitty’s elder sister Maria who was professed as a Loreto nun in 1906, known by her name in religion as Sr Columba. She wrote the lyrics of what became a well-known political ballad: ‘Who Fears to Speak of Easter Week.’

Kitty, a member of Cumann na mBan, was part of the organisation of the massive drive of support for families of those imprisoned after the 1916 Rising, as Trustee and Secretary of the Irish National Aid Association, and considered as one of the most active members. She was involved in the anti-conscription campaign and also took part in the re-constituted Sinn Féin movement and the electioneering drive for Sinn Féin candidates. She stood, unsuccessfully, in the 1920 election for Dublin Corporation, but did get elected as a Poor Law Guardian. Throughout this period her husband spent time in prison.

By 1920, the couple and their five children Kevin, Aidan, Eithne, Colm, Feicín were in America, and a sixth child, Róisín, was born there. Their arrival was welcomed by Irish Americans and a reception was hosted for them by the Irish Club of Philadelphia. Within a short time of their arrival Seamus O’Doherty had taken over managerial and editorial control of the Irish Press. Kitty assisted him with managing the newspaper and wrote articles. She also established the Irish-American relief committee and coordinated the sending of relief to Ireland in the form of clothing and medical supplies. She was involved in the fundraising bond drive. She formed a Women’s Auxiliary of Clan na Gael. Kitty also met with prominent Irish Americans on the issue of the Irish cause, addressed Irish American women’s groups and others including Indian nationalists. She was part of picket protests organised in the city. Later she would write of this time in Assignment America, published in New York, 1957.

The couple remained politically active during this period, and when the Truce came, according to Dr Hughes, Kitty and Seamus were in the inner circles of people who would have shaped the negotiations for peace and their outcome.

Lizzie Leonard

Delvin and Mullingar

At the time of the Truce, Lizzie later recalled, her work for the campaign of independence was the same as usual, as they awaited the outcome of talks in London.

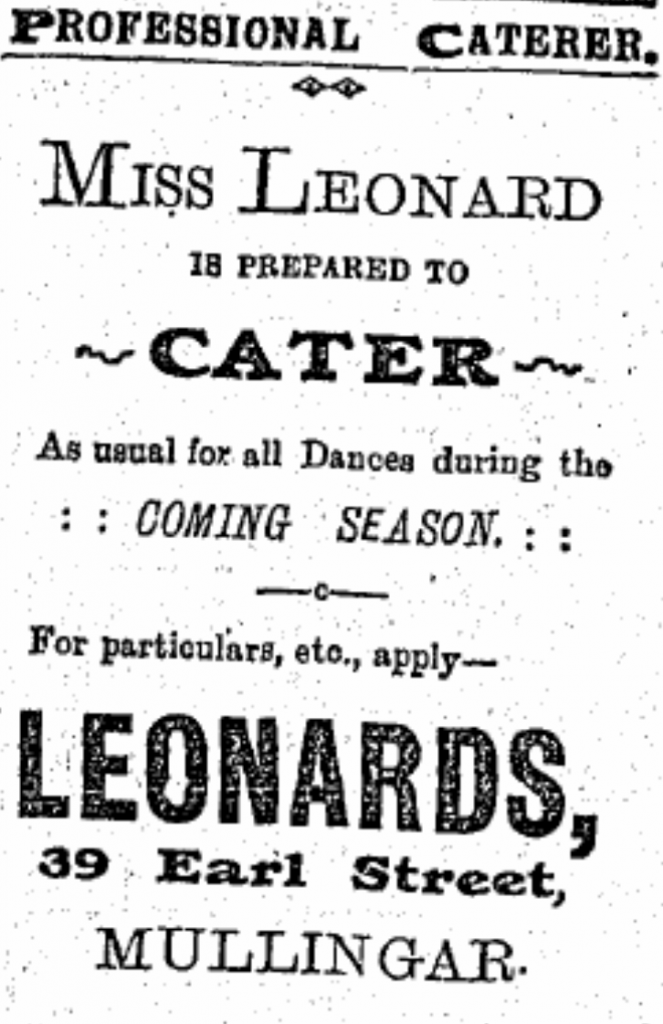

Lizzie Leonard and her sisters grew up on the farm at Ballinvalley, Delvin. In addition to farm duties, Lizzie trained as confectioner, and when she was unable to find employment, she set up her own café at 39 Earl Street.

In the aftermath of the 1916 Rising, Lizzie joined the reorganised Cumann na mBan and her role in the campaign for independence was anti-conscription activities, electioneering, and looking after the needs of prisoners. A number of the family became active. Her brothers Edward (Ned) and Patrick were members of the Delvin Company, 4th Meath Brigade, IRA.

The Leonard farm and the café became centres of activities, and were well known to the Crown Forces. There was a raid on the café in January 1920 in the search for a ‘man on the run’, it was reported in the Irish Bulletin that 30 armed police had entered the premises. Her brothers were arrested in 1920 and held in Ballykinlar Camp, County Down. The sisters were under constant threat of their premises being burnt. ‘In a generation of brave women,’ recalled one contemporary, ‘she deserves to be numbered among the best.’

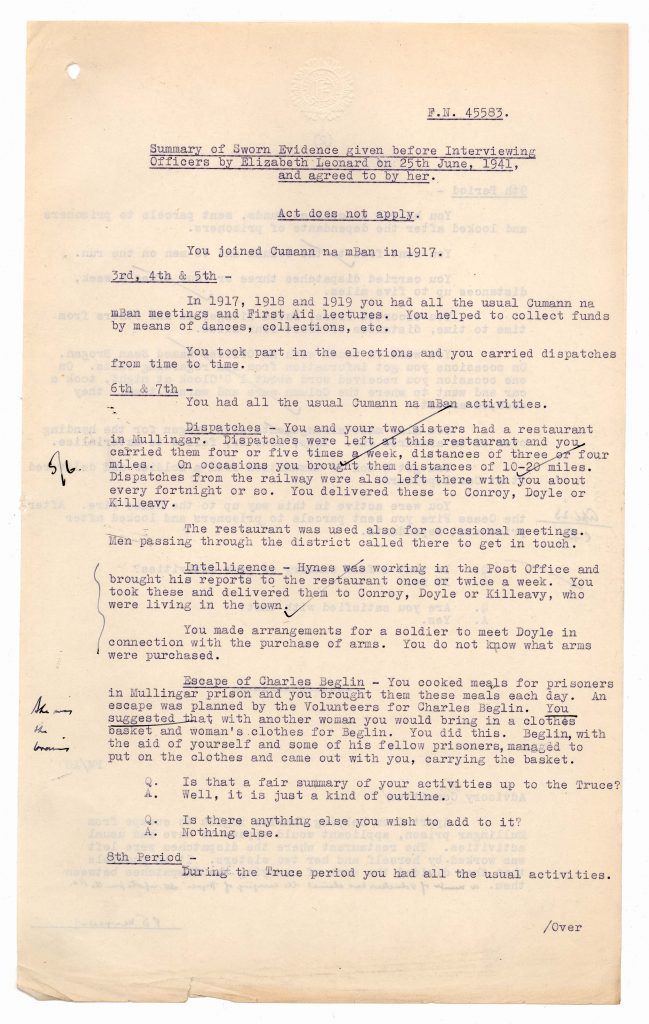

In March 1921 Lizzie was heavily involved in an operation to liberate a Mullingar IRA officer, Charles Begnall, from imprisonment in Mullingar military barracks. She outlined what happened in her Military Service Pension Application:

Eileen McGrane (Later Dr. Eileen MacCarvill)

In July 1921, when the Truce came into force, Killucan native Eileen McGrane was in prison in Walton Prison, Liverpool, England. She was one of Michael Collins’ key agents. Her flat at 21 Dawson Street had been raided on New Year’s Eve 31 December 1920 by 15 members of the RIC’s notorious Auxiliary Division. Her youngest grand-daughter Marika MacCarvill details the story of Eileen’s arrest, trial by Field General Court-Martial held in the North Dublin Union on 12 May 1921 and her deportation to Walton Prison in Liverpool on 25 May 1921. In this piece Marika MacCarvill outlines how at Eileen McGrane’s trial she was convicted of having possessed weapons rather than the being convicted for the discovery of incriminating documentation held in her flat, which detailed her involvement in the intelligence network. Watch this short film and discover why Eileen McGrane’s true role was concealed … as the Truce negotiations were underway.

With special thanks to Marika MacCarvill, the MacCarvill family and Melanie McQuade, Heritage Officer with Westmeath County Council.